Passover 2016

The night before Passover, about to dip a hunk of sourdough into olive oil, I started to smell a memory; hunting through the darkened house with my grandfather and a candle, a feather and a paper bag. In an inside-out retelling of Hansel and Gretel, my grandfather and I sought the crumbs hidden in corners by my grandmother.

That was very long ago.

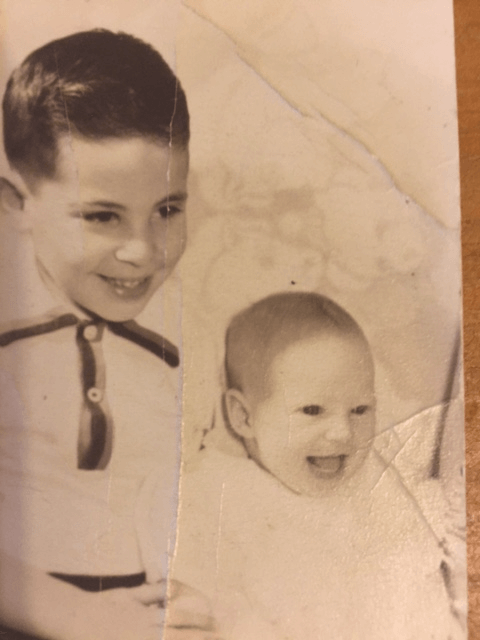

I was as mystified as a teenager just as I was as a precocious baby.

The next day, I was in Long Beach with my mom. Just the two of us instead of the crush of relatives decades ago. We headed for seder #1 at the hotel down the block. At our table, the parents of a boy who used to have a crush on me when I was in Yeshiva at H.A.N.C. I hadn’t seen them for twenty years, having bumped into them after gorging on onion rolls at Ratners.

He still held on to his I-was-a-well-regarded-chazan self-esteem. As he pushed the walker, his mentation was far, far behind. She was a still stunning—think Leslie Caron—survivor of Buchenwald, and she told stories. One of the evening’s highlights (it certainly wasn’t the food, or the Netofa red—I missed the rusticity of a few years back) was Leslie’s tale of her husband’s paranoia; how he scuttles with his walker to look under the bed, then rushes to the window to catch her lover racing away in their ‘fuck-mobile.’

I laughed unapologetically, wholeheartedly, mirthfully at her three-dimensional storytelling. And she met me with toothsome laughter. It was a moment. My mother didn’t know what to do so she went back to the gefilte fish.

That night Mom had a very impressive GERD attack. The next day she did not go to shul. The earth has to split for her not to go to shul. And when I visit her, the only way I get out of going to shul—which is always the goal—is if she doesn’t go. Spent from recent travels, still sick, I indulged in the cloak of the holiday and out of respect of my mother’s orthodoxy, disconnected from devices. So, I slept deep and long except for getting up and rifling through the papers that still live in her dusty closet, always looking for who I used to be.

Letters. Papers. Diaries. They were psyche ripping. In fact, my seams are still torn apart. Looking over college papers I realized I couldn’t construct a sentence or build a thesis or argument. I couldn’t spell (I still cannot).

Was it my undiagnosed dyslexia? There I was left to deal with it on my own, back in the days when the dyslexic believed themselves to be stupid. Which of course I was. How could I not be?

I was the original “I’m faking it.” I didn’t write, I didn’t build, there was no logic or thought process. I suffered, I was uneducated or was I merely ineducable? My ideas spewed like molten lava flowing and blobbing out of Mount Etna. That was me. If only they taught Latin in yeshiva instead of Hebrew, it might have helped. Instead skated on with that infant-like precociousness but by the time I landed in Stony Brook, I was lost and no wonder I danced, it was the only structure and discipline I understood.

I progressed on to my brother’s letters. “Dear Mouse,” he wrote from his hell-hole sentence when in Manila, in medical school. I forgot that years after I stopped being called Mouse, he still wrote to me as Mouse. I forgot that he used to also address me as Dearest Sister Alice—invariably followed by, you asshole, you shmuck, you… whatever and then the scolding of my inability to find a Jewish man or my stupidity of the heart.

You had to be there. It was all done with love.

I forgot how he played ragtime in the whorehouses for tips and bowls of squid—he fed to the dog. How his roommate actually went to them, and how Andrew had to “jab his pimply ass” with penicillin when the roommate contracted The Clap. I would love to ask him about the whorehouses, and why exactly he hated Manila so much—the days of Imelda and the shoes…so long ago. But he’s not here. And the letters are a poor consolation but they help to deepen the layers of what exists of our connection.

I took my letters and even a diary which proved that I was a far better writer when I was 14 than when I was a senior in college. I took my brother’s letters as a testament that someone loved me and took me seriously, even if I couldn’t write or think. But what I certainly excelled at was feeling.

I shouldn’t care about who I was back then, before I became this thing, this wine writer, but I do. There’s no going ahead without looking back. T.S. Eliot in all of his difficulty had the lifeblood in his hand, embedded in Little Gidding.

What we call the beginning is often the end.

And to make an end is to make a beginning.

The end is where we start from.