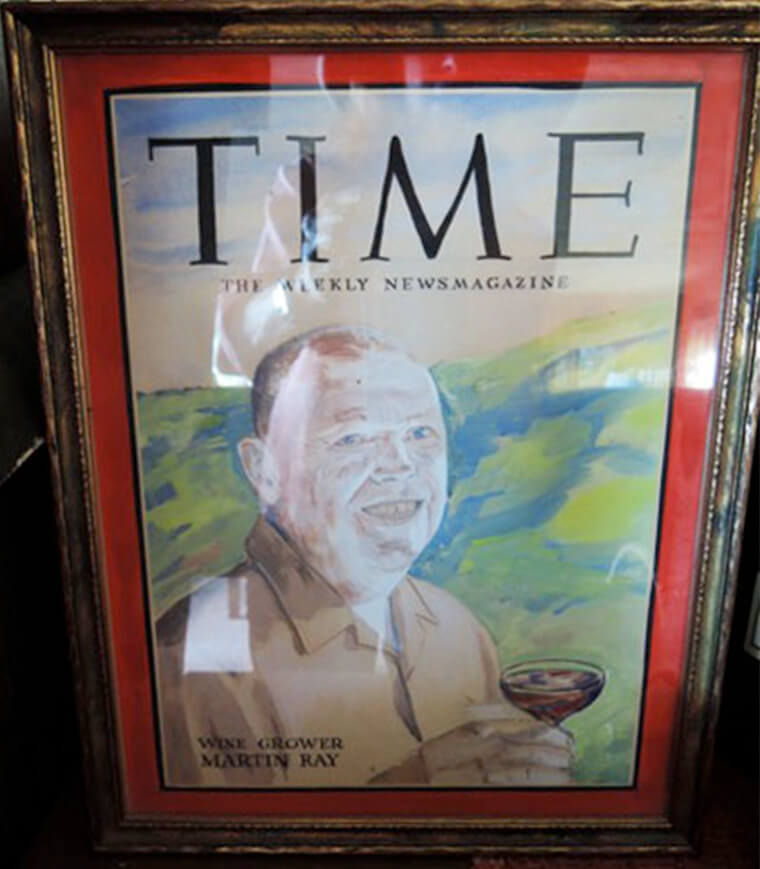

In case you think Martin Ray is the name of an avoidable winery in Sonoma, stand corrected. Martin Ray is California history and the reason there’s the current lust for domestic pinot.

Best of TFL: Channeling Martin Ray

Martin was an iconic visionary and an advocate for 100% varietal wines from worthy vineyards. He railed against manipulation and begged for appellation designation. Like many of the passionate and opinionated, he was a pain in the ass, a loner and generally viewed as a difficult nutcase. His first vintage from his Santa Cruz vineyards was 1935 and his last was 1974. While he yeasted he never added a drop of sulfur. “We add nothing to our wines, nor do we take anything from them,” he said in an interview before his death in 1976. The real Martin Ray was a legend and an American wine hero. My kind of guy.

His wines were rumored to be unpredictable; some said one out of ten were drinkable, though that bottle might have been sublime. I yearned to taste, but had given up hope that a kindly collector would make that possible. That’s okay. In 2011 Martin’s heir and stepson Peter had given Duncan Meyers and Nathan Roberts the great honor of buying the grapes from that very vineyard. I could make do with the lovely Arnot-Roberts pinot. In addition, this May, Duncan and Nathan made good on a promise to take me to see the piece of land in the sky that started it all. Eager to see this slice of American wine history, I eagerly set aside the day. If I couldn’t taste a Martin Ray original, I’d channel its spirit.

Twisting up the mountain, past some of the newest McMansions that had invaded the peace, we arrived at 1400 feet to step out into the freshly tilled, garden-like Peter Martin Ray vineyard planted to Cabernet and Pinot Noir. Peter had just been in town to disk and plow the land. Around 80 years old, and living in Washington State, he insisted on traveling to the mountain yearly to do the job himself. “A horse would be gentler.” Nathan commented wishing the organic vineyard was less compacted, but Peter was attached to his tractor.

I stood with my hands on hips, the wind blowing, and looked down at scalloped vineyards. The perfume from the vine in flower teased my nose. The dry-farmed grapevines stood up individually, like soldiers. Each had been tied to a single stake, like the northern Rhone echalas but with a floppy, top heavy, California sprawl. The soil was broken reddish soil, Franciscan shale, the kind that Martin Ray referred to as “rotten rock.” I could almost feel Martin, whose ashes had been scattered in the soils in 1976.

“This 2.8 acres only gives you three tons?” I asked, envisioning the three tubs of fermenters in their Healdsburg winery. “There’s virus,” Nathan explained, referring to leafroll virus which reduces ripeness and yield, causing panic among so many winemakers looking for greatly developed sugars, “We actually think loss of ripeness is not such a bad thing,” Duncan added.

It was hot out there and conventional wisdom would say far too hot for pinot, yet the wines had never been acidified. The new A-R Martin Rays are zippy as well. Something about the place defied wine logic. It was a mystery or was it merely those deep roots through the rotted rock, or the schist/shale’s air-conditioning ability? We were hot too, and thirsty so we retreated for a snack on the porch outside the humble ranch where Ray had staged legendary parties. Duncan and Nathan pulled out a small picnic, crumbly cheese and lentil salad and an assortment of new vintages. Then came the not quite released 2013 Martin Ray. The pinot was respectful, full of spicy stems, foresty rich and pretty. That’s when another bottle was extracted from their magic wine box. The men had brought along a dream of mine, about to be fulfilled, the 1962 Martin Ray pinot noir. Martin sat right down next to me. I know he did.

“Maybe it will be good, maybe not,” Nathan said and then Duncan tried to snaggle the cork from the bottle as I said to myself, thank you Duncan and Nathan. Thank you. Thank you.

There’s not a lot written about the way the wine was made. I could ascertain through Martin’s interviews that the wine would have been crushed and fermented on the seeds and stems, poured into 200-gallon wooden fermenters, half-filled. Inoculated with Montrachet yeast (he was convinced that he needed to) gently punched down every three hours. Then pressed off in a basket. There was no sulfur at any stage. The reds aged in barrel for about three years until stable in from what I could tell was a relatively warm cellar.

Duncan worked the cork. He cursed. We held our breath. Finally with some difficulty and fracture the cork came out, wine poured. I wasn’t the only one quivering. It was alive.

“That’s legit!” declared Duncan.

The color was like tomato water. The taste ping-ponged from bright to leather to Band-Aid to delicate to intense to gorgeous, to alive to electric and mushroom power and back to Burgundy and then to the moon and then to the umami of Japan and the acid was out of control. This was the kind of moment we all chase. That moment of greatness when the history, place, and power come into the glass. Without that wine, Duncan and Nathan would not be making the wines they do today. Martin may have been difficult, he may have been mad, but there was conviction and genius in that glass.