The hour drive to the southern Jura from Beaune became progressively quainter as urbanity melted into the tiny stone villages. Finally, it opened up into fields, cows and a few vineyards. The last time I was in those parts, the lanes were sheeted in black ice. Snow coated the hills. But in July of 2019, in the valley between two mounds of heat waves, all was brilliant with lemony sun and puckery blossoms. With me in the car were the Chantrêves winemaking duo, Tomoko Kuriyama and Guillaume Bott and a long-time friend, Paul Wasserman, of Becky Wasserman Selections. We were headed to visit Japanese ex-patriot vigneron, Kenjiro Kagami. I was extremely happy about this outing because after three failed attempts, I was finally due to visit the elusive vigneron at 3pm.

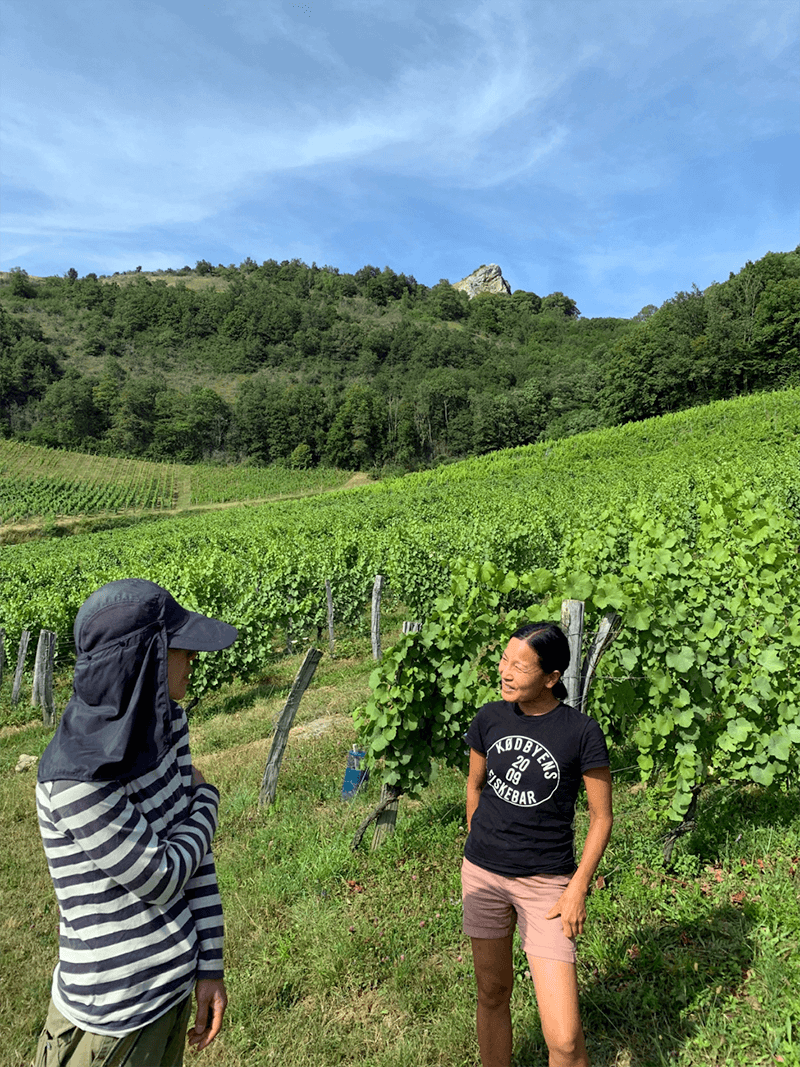

We were early. To avoid being rude we parked a few minutes away and stretched out on the tender grasses by the banks of the creek as the fluorescent blue dragonflies hovered. “I worry about him,” Tomoko said, looking out at the pristine babbling water, “Kenjiro is very committed to no-till,” she said, mentioning what might be the most talked about trend in farming vines. “It works quite well of course. But the last time I was there, that piece of land, up near the forest, on a steep slope, really looked sad. I just don’t see how he’s going to get any grapes off of that section if he doesn’t turn over the land. He needs to make money. Well, we’ll see!” With a clap of her hands as a signal, we brushed off our pants and headed back to the car.

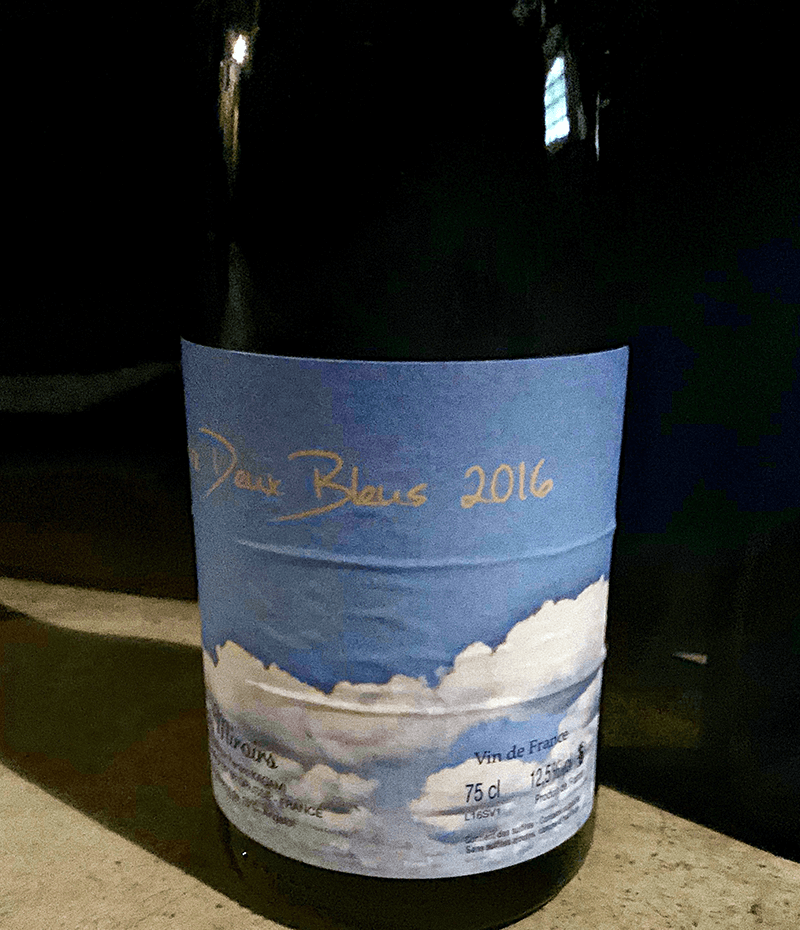

Even before Domaine des Miroirs debuted with the tiny 2011 vintage, Kenjiro was practically mythical. The ex-Hitachi engineer took an interest in wine in the late 90s and followed his heart to Beaune to study winemaking. He longed to work with grand cru vines and especially lusted after Musigny and limestone. He landed his dream job for de Vogüé as his stage and worked there almost daily, as school was merely once a week. His resumé evolved into stints with a trio of natural legends: Thierry Allemand in Cornas, Bruno Schueller in Alsace, and Jean-François Ganevat in the Jura. It was Ganevat who found him his land in nearby Grusse, a village with the same number of residents now as in the 1700s: 185.

I drank my first Miroirs in about 2014. It was most likely that initial 2011 vintage. Although I didn’t love the chardonnay with its acidic, milky reduction, there was something in there that just didn’t let me forget it. I went out of my way a few years later to meet the vigneron at a tasting in Paris. Formal, dapper, a silk scarf tied deftly around his neck, he put up with my French. It was there that the wines grabbed me as being somewhere between heaven and earth, between wine and the rain, between there and not, some sort of blindfolded trust of balance. I came away wondering whether it was wine or something else entirely.

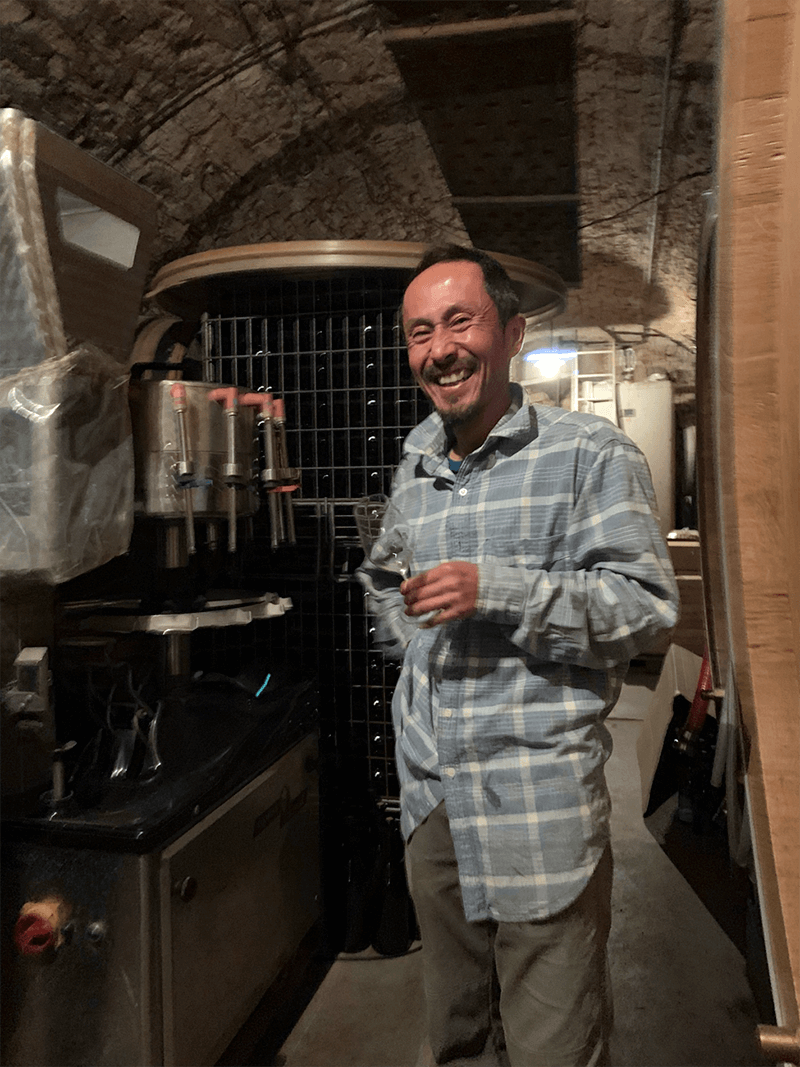

We pulled up to a rundown farmhouse right on the road and pushed in the weathered doors. Inside there was a pre-harvest mess: a small pneumatic press, barrels, bottles and not much room to move around. We opened another door to find Kenjiro in a brick-arched long and narrow barrel room. A slight, bearded man in clothes a size too big, he reminded me of a high school kid cleaning out the garage. His treasures were fermenting and aging in two large, red-banded barrels as well as old barriques stacked two and three on top of each other. The barn was leaky and a little warmer than optimum for natural winemaking, I thought. After the hellos and the immediate distribution of INAO tasting glasses, a shyness settled over the room. But as soon as French was swapped out for Tomoko and Kenjiro’s native language, animation kicked in. All of the sudden Kenjiro smiled broadly. “What makes you smile?” I asked and Tomoko answered, “The cuverie is filled with wine for the first time.”

It must have been a remarkable feeling of relief and perhaps a bit of triumph. Usually Kenjiro’s yields are terribly low with no more than 25 hl per hectare. This adds up to maybe 10,000 bottles a year if he is lucky. But in 2018 there was the potential for more than double that. Finally, there was some wine to sell around the world, not only Japan, Denmark, France and England.

The vigneron scampered up the barrels with a pipette. He drew out the wine and then silent and cat-like, he jumped down from the top, landing thudlessly, spilling not a drop. He started to explain his methodology. The first few vintages he used to start fermentation by making a pied de cuve. This, a little test batch of natural yeast ferment is one way traditional winemakers kick off fermentation. Now, he just waits until each of his vats take off. “The wine just cooks,” he says.