By Sophie Barrett

Best of TFL: Reduction Reduction What’s Your Function?

They say that you can fix a reduced wine by dropping in a copper penny, which may or may not work. Sure, try it, but meanwhile, come along as ex-New York wine personage Sophie Barrett plummets down the rabbit hole of reduction.

Once upon a time, I was at dinner with two biodynamic growers in the Haute-Savoie. Tasting Chasselas from the French side of Lac Léman, I noticed a familiar aroma of freshly lit match on a stone. Alpine mineral wafted from my glass. “C’est reduit,” one of the growers commented, “mais c’est la reduction du vigneron!”

He was talking about the familiar sulfury stink we normally associate with a wine that needs airing, that hasn’t been racked, or is closing in on itself. Reduction shows itself as aromas generated by sulfur compounds. General descriptions include rotten egg, burnt rubber, skunk, burnt match, asparagus and the mercaptan smells of onion and garlic. But I’d never heard it expressed as “winemaker’s reduction,” something a vigneron would actively cultivate.

Well, that’s not totally true. I had noticed sommeliers referring to the struck matchstick smell that would appear in certain vintages of the renowned Burgundian domaine Coche-Dury as “Coche reduction.” But this was a wine that was unobtainable and out of my price range, so never having experienced it, it wasn’t much on my mind when I first heard the phrase la reduction du vigneron.

This statement of winemaker’s reduction, however, was very much in my mind when, not long after, a situation arose with a customer that made me look deeper into the idea that not all reduction is the same and some types can actually be positive.

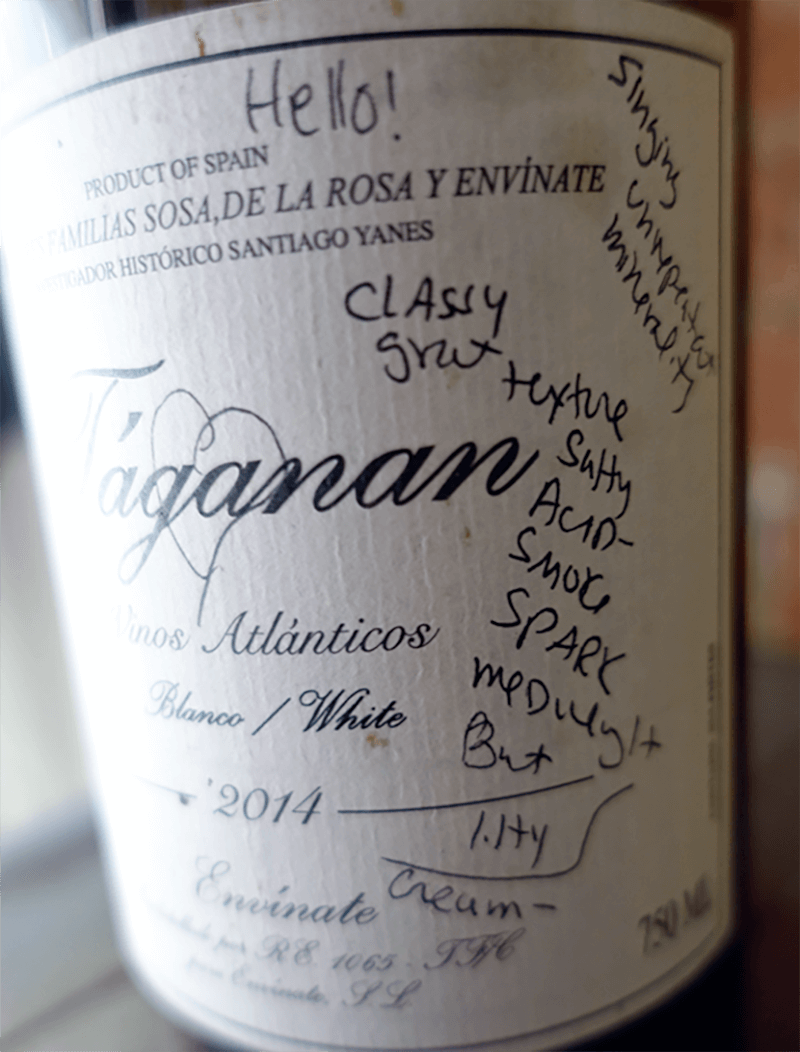

The situation was this: a customer, a well-regarded sommelier, returned his allocation of 2014 Envínate Táganan Blanco, saying the wine was too reductive, that he couldn’t serve it, and would have to send it to the kitchen to cook with. Questions came up for me: would the reduction eventually recede? If so, when? Was there a problem in the winemaking that perhaps, the well-worn salvo, a well-timed racking would have fixed? It puzzled me that reduction could a be flaw, a pesky byproduct of natural wine and a virtue actively cultivated by star winemakers. In Coche it was good. But in the Táganan it was bad? Did folks realize that the lofty Coche Dury Effect was really just reductive winemaking—and not some magic genie in a bottle trick that made it somehow worth $700/bottle?

And with that, I plummeted down into the deep rabbit hole of reduction.

For sure, that 2014 Táganan Blanco is amongst the most reductive wines I’ve encountered. Yet at the same time it was brilliant. I’d decant it 30+ times then leave the decanter for hours trying (without success) to air out the matchstick smell. But here’s the thing, it didn’t carry through to the palate, which was gorgeous. For me, it was a wine clawed from the earth with vivid yellow fruit. For my customer, it was unacceptable.

Turns out that Envínate’s Roberto Santana is actively trying for reduction in the wine. While he’s looking for it as a byproduct of grape and soil (“For us it is very important to see the potential of reduction in the wines to be sure that our wines are protected of oxidation.”), he’s not forcing it in the cellar via sulfur additions and inert vessels, such as stainless steel. He’s adopted a style of reduction management that favors terroir expression alongside ageability.

I tried the question of good reduction and ageability out on another great wine brain: Chad Stock of Craft Wine Co. in Oregon (Minimus, Omero Cellars, Origin). Chad has played with reduction, he even named a wine after the process, his 2011 Minimus Wines #5 Reduction. “There are certain forms of sulfide reduction,” he wrote, “that manage to undergo a transformation process in which they resolve themselves over time, and during that time of resolution consume large amounts of dissolved oxygen in wine, which slows down the oxidation of fruit and other aromas that we associate with youth and freshness.” Essentially, a healthy sulfide reduction, when coupled with slow, controlled oxidation creates “a long haul wine, something that will age, a winemaking holy grail.”

Subsequent vintages of Táganan Blanco have been less reductive than that 2014. Curious, I asked Roberto what he’d done differently and his answer was as thought-provoking as the wine. He talked about carbon dioxide.

With the 2015 vintage, they began to measure the amount of dissolved carbon dioxide in the wine before bottling. (CO2 is a byproduct of fermentation and is another “natural tool” that protects the wine against oxidation and fosters long life.) Based on this number, they’d make the decision to aerate (rack) the wine before bottling or not. Thus they were playing with levels of two natural protectants, dissolved CO2 and reduction, to create wines “with good potential of aging, but also wines of pleasure from the beginning.”

Going further down the rabbit hole, I learned from Johannes Weber (of Hofgut Falkenstein) that there’s a clear rapport between spontaneous fermentation and reduction. Spontaneous ferments use a larger number of microorganisms than cultured yeast ferments. These microorganisms require nitrogen to reproduce. Nitrogen and sulfur are among many molecules found in amino acids. When yeast metabolizes certain amino acids in search of nitrogen, it “sets the sulfur free,” Johannes said. “It can then react with other components in the juice/young wine and starts to smell like burned rubber, egg or even worse.” These sulfuric compounds are unstable; if exposed to oxygen, they react. This is why winemakers rack or pump-over to aerate a reductive ferment. This is also why when you get a stinky wine you swirl or decant. It helps. At its most basic level, reduction is a lack of oxygen.

If the stainless steel tank is the poster child of mediocre reductive winemaking, fine lees are the heroes of the good version, notably because lees-aging is generally used in tandem with oxidative processes (like barrel aging) to promote balance between the two forces. Utilizing lees to protect against oxidation is an age old practice. It’s become increasingly fashionable and is now widely considered to be beneficial. These days winemakers favor long, tranquil periods of lees-aging (no stirring), Sleeping Beauty awaiting the bottling.

While winemaker’s reduction tends to be about choices in the cellar (Tank or barrel? Lees or no? Stirred or not? To rack or not?), there are other factors: grapes, and even soil.

Grapes themselves can have different proclivities for reduction, which dictates, or at least suggests, how to handle them in the cellar. Reduction helps build structure for the future. Eric Texier says it’s folly to vinify syrah or côt in an oxidative way. Reduction is a necessary—but by no means sufficient—quality for aging. On the other hand, reductive grenache ages “very badly.” Is this a chicken/egg conundrum? Are some grape varieties inherently reduction prone, or are they vinified reductively because that’s what works? In the case of the following varieties, many (perhaps the majority) of the best examples are reductive when young: Syrah, côt, mourvedre, carignan, poulsard, trousseau, gamay, chenin blanc, listans negro & blanco, the list goes on.

While we tend to think reduction is born and bred in the cellar, the more winemakers I spoke to, the more convinced I became that reduction is born in the vineyard. As I learned from Chad, “poopy” reduction, the kind that leaps out of a fresh bottle of poulsard or côt, is directly linked to spraying sulfur on the vineyard too close to harvest, or an amino acid imbalance in the juice: “Elemental sulfur plays a large role in reduction during fermentation so spraying too close to harvest is never a good idea especially in dry arid climates.”

Picking choices factor in as well, especially now as climate change provokes winemakers to pick earlier in search of higher acidity in the grapes. Early picking seems to result in more reduction. Chad’s theory on this is two-part: grapes picked earlier have less nutritional value, meaning less yeast-food, thus greater chance of yeast gorging on sulfur-containing amino acids. Also, an early pick may mean less time between sulfur spraying and harvest, therefore more elemental sulfur in the juice. Is it coincidence that high acidity and reduction have come into fashion in tandem? With early picking, a winemaker can have both!

Having noticed reduction in many of my favorite Canaries wines, I asked Roberto Santana if he thinks soils play a role. Táganan Blanco is a field blend, so we’d be hard pressed to pin the reduction on a particular grape. Roberto’s response: “For us the volcanic soils at Canary Islands have a lot of personality and for us have more tendency of a little reduction. We think it is more related to the soil than the grape variety, and of course in the cellar—if you work with products (commercial yeast, enzymes, etc.), reduction should disappear but along with it the personality of the terroir. That’s not the deal for us!!!” This is to say that when reduction is an aspect of terroir, let it live on in all its sulfuric glory!

I passed this question along to Chad, who reported similar findings amongst the terroirs he works with. “Granitic and volcanic soils in my experience present the most reductive expression in the Willamette Valley and in the Applegate Valley. The basalt in Oregon is particularly intense but its generally noble reductive qualities increase the life of a wine.”

Johannes sited rocky soils as more likely to give a reductive wine because “they lead to a grape juice that is lacking nutrient for the yeast to ferment that juice. The yeast metabolizes everything it can, also amino acids with sulfur components. And we are off to a reductive wine again.” Chad echoed this sentiment almost verbatim, adding that this type of H2S specific reduction is more common in inoculated wines “due to lack of proper nutritional value matched to the yeast chosen for fermentation.”

Digging deeper into reductive soil types, I sought out Benoit Courault in Anjou. Benoit works several plots of old vine chenin on schist that were previously farmed conventionally. I was certain he’d tell me these particular soils were nitrogen deficient and yielded a more reductive wine. What he in fact told me was, sure, nitrogen can play a role, but thanks to elevage and racking, reduction disappears.

Benoit, though, went ahead and made this trenchant observation: limestone has a very aromatic side; it’s a flatterer amongst grapes. Next to it, more austere soils such as granite and schist can make us think of reduction. It’s easy, even for experienced tasters, to conflate aromas of terroir with aromas of reduction, especially if the two appear hand in hand (Táganan Blanco, anyone?). As this “catch-all,” reduction is grouped together with all the different off aromas trapped in the bottle, as well as the deliciously musky, sulfurous smells of certain more austere soil types. And then there’s also the hand of man, especially when man aids in depleting the nitrogen. In Texier’s words: “Crappy farming helps (with reduction)! High pH + bad work with lees = high reduction.”

Complicating all of this was, and always will be, fashion; from the lees-stirring that made so many 1990s white Burgundies undrinkable, to the lean, matchstick, ‘sleeping beauty’ style that followed it. Blindly following fashion never seems to work out. Learning from the trend is quite another matter, such as when the winemaker separates the good bits like native ferments and lees-aging, from the less good bits like inert aging vessels and screw caps.

Recently I opened one of my remaining bottles of 2014 Táganan Blanco. Anticipating the matchstick, I popped it in the fridge, cork out. An hour later I nosed the wine…not a hint of reduction, just porous, soil-y notes, preserved lemon, and a whiff of smoke. I pondered the wisdom of winemaker Roberto Santana followed by the folly of my customer who returned the wine. Emerging from the rabbit hole for a draft of fresh air, I sipped from the glass with renewed wonder and admiration.