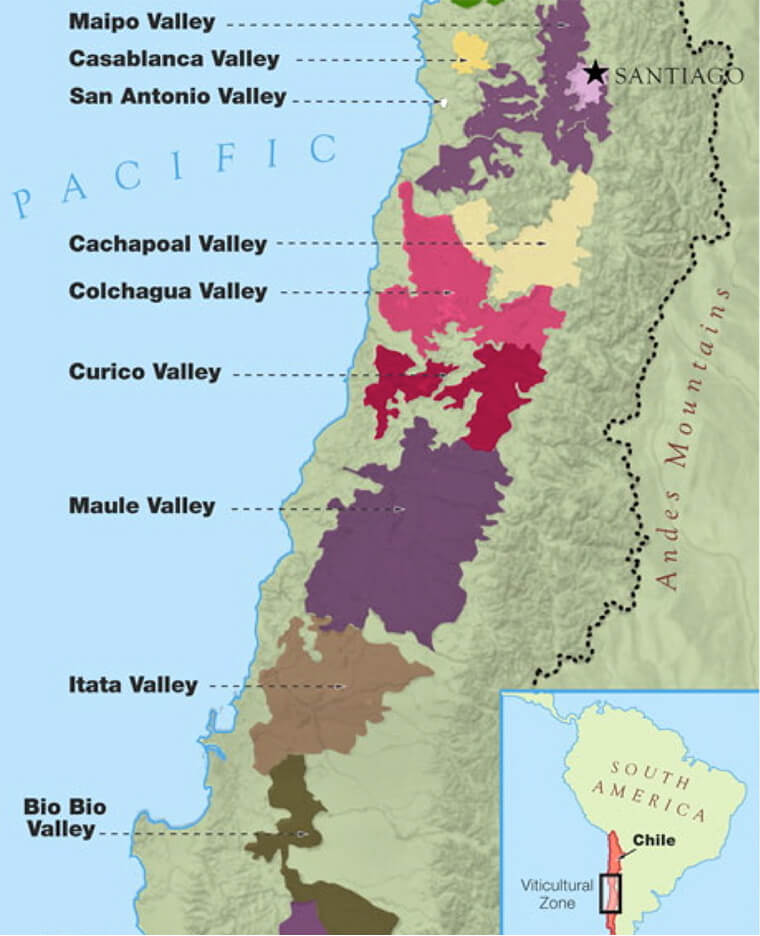

The summer sun was strong as Mauricio Gonzalez Carreño hacked through his unruly país with his machete. Those vines were in Yumbel, which lay in the bowl of Bío Bío of the Southern Chile region. Framed by the looming Andes and the volcano that made his soils, it had been abandoned for a quarter of a century.

While he’s bringing back cultivation, many grapes still ran wild. And so did the other fruit. The place seemed to have been blessed by the Chilean Persephone; there was so much abundance. There were plums, sparky cherries, and snappy apricots. His wife pointed out maqui, one of the world’s most intense super antioxidant berries that put gojis to shame. Stuffing myself along the way, we circled back to the cantina. It was immaculate and spare. No pumps. No tricks. It was the opposite of the nine years of corporate winemaking he left behind in Mendoza to come back home and make a simple wine called pipeño.

Mauricio is part of the Asociación de Productores de Vino Campesino de Chile, organized by natural wine advocate and sommelier Macarena Lladser. Their group of four all practice within the wine regions inside of the Secano Interior. They dry farm their organic land and mostly old ungrafted vines. Devoted to low intervention winemaking, they are committed to revitalizing the local heritage of pipeño, a refreshing wine low in alcohol, made from the disrespected grape país, raised in pipas (get it?)—barrels made from local beechwood called raulí. While the press often describes them as Chilean Beaujolais, I find the best are thirst quenchers but with the backbone of mencia. Very easy to love, they are far from the Chilean wines I rebuffed for a long time.

The brilliant brick-colored granite-based soils of Roberto’s vineyards.

What didn’t I like about Chilean wine? The use of irrigation. The flat lands instead of the slopes. The embracing of the grapes of Bordeaux and Burgundy. A pandering to commercial taste. I knew there was terroir—the country was under the influence of the dramatic Andes and the salty air from the Pacific. The old vines were impressive.

Yet, look at any Chilean wine promotional website, and you’d believe that the country never had much of a taste for wine until new invaders from France, Spain and California showed them how to treat their grapes. No mention of país for that matter. Even if you look at Jancis Robinson, you’ll come away with the same conclusion. That is enough to get the Asociación angry as hell. Because país once ruled the Chilean hills.

Also known as mission or listán prieto, it arrived in Chile with the Spanish conquistadores, possibly through the Canary Islands. And while they had been making wine for hundreds of years, like Etna, their country didn’t have a tradition of bottling wine, though drink they did. But with Pinochet, wine was suppressed, and that’s not something often talked about outside of Chile.

I was determined to get someone to talk to me about it. Upon arrival in Concepción, the city five hours south of Santiago, Roberto Henríquez, the adorable man-bunned winemaker, picked me up. With the cool Macarena holding on in the backseat, her cigarette dangling out of the window, we headed out to see his vines with a tour of the remaining hiding vines in backyards and patches. I asked what the Pinochet effect was on the region. Roberto’s jeep jiggling along the terrible roads that led to his país vines, he pointed out the carpet of pine trees and eucalyptus. Eerie in its monotony.

In 1974, the “forest development” law 701 offered incentives for replacing native trees with invasive pines and eucalyptus for the paper industry. In particular, the eucalyptuses were water hogs and in the brittle heat of the summer increased the impact of fires. The direct effect was the retardation of the wine industry, shrinkage of vineyards and the vanishing of indigenous animals. The remaining patches of vines hid up the new trees or grew in backyards as head-trained globes. Yes, those trees were trouble. Roberto, and just about anyone I met who cares for the land and vine, hated those trees with nationalistic passion. They were a threat not just to the autochthonous animals, but to the region’s cultural identity. “They will create a disaster,” he said presciently.

Those are Roberto’s vines struggling for their future under the pines.

But to go any further in the exploration of the renaissance of real Chilean wine and pipeños and not bring up French ex-patriot Louis-Antoine Luyt would be colluding with more revisionism. Many years ago, on a besotted night of wild dancing in Tribeca, the lovable man, and a veritable pogo stick, shared with me the story of the pipeño renaissance.

Sometimes it takes an outsider. Louis-Antoine, the French force who first championed the real local wine.

In his pre-heroic days, Louis-Antoine at 22, decided Chile looked like his next home. His three-month visit became permanent. He worked his way up the restaurant ladder to sommelier. In 2001, he returned to his native Burgundy, France to work harvest. Philippe Pacalet led him to Marcel Lapierre and the groove with all of the other local natural wine guys. When Louis-Antoine returned to Chile, the wines he brought to the capitol were influential. Tastes started to change. But more importantly, he decided to make wine. He looked around him and said, país? Is there a problem with the grape? He knew there wasn’t.

Louis-Antoine gave Chile its first exported natural wine in 2007, Clos Ouvert. He started to make wines under his own name from rented vines. But then, impressed by the work of the campesinos, he sought to preserve their traditional methods of fermentation. The first commercial export of pipeños was born, and the world slowly started to get used to the idea that Chile wasn’t all about heavy, syrupy cabernet. The wines first made a market in the States and in Europe and laid the path for Roberto and the others coming back to tradition.

The week after I arrived home, on Instagram I saw a terrifying picture of Roberto’s vines with crimson shadow of fire, encroaching on his país. The legacy of Pinochet revisited, just as Roberto had feared. But who knows, perhaps one day, along with the país and the pipeño and the real wine, the forests, too, can once again become real.