To recap from part 1: The penultimate white grape of the Loire, contrary to popular belief, is not sauvignon blanc, but the other blanc: chenin.

That late ripening grape flourishes in Anjou’s two habitats: the white (limestone) and the black (schist). If you’re like Michel Bettane you might despise the ones from the schist. If you’re more like Pascaline Lepeltier and myself, we go equally for both. Those from limestone seem more angular—because the soil may help them resist the edge-smoothing malo. On schist, where the wines tend to naturally go through the malo, the wines are rounder. But that’s a simplification and the other nuances need to be examined.

So, based on a conversation Pascaline had with her mentor, Patrick Rigourd, we revisit the topic this month. Sitting at my table she shuffled through her extensive notes, pulling out the nuggets. Basically there are three issues besides the malo: water stress, reduction, and botrytis. (Put your science hat on—things are about to get technical.)

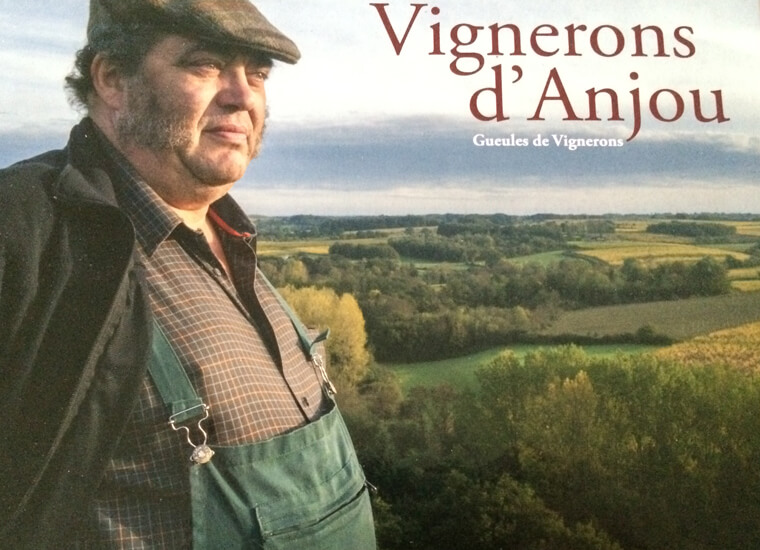

Jo Pithon graces the cover of Rigourd’s new book

Water stress: Where there’s more clay mixed with the schist there is more water stress drying the soil, making the vine struggle, concentrating the flavors, sometimes resulting in higher alcohol levels and thicker skins. The phenolic maturation of skins and seeds is speedier and riper on slate than on limestone. The resulting wines will show more varietal characteristics, which they call Chenais. That means they’ll show more straight grape flavor and bitterness, rhubarb and quinine.

Reduction: You know the way syrah can have notes of animal and rubber? That’s what is referred to as reduction, or the appearance of ‘reduced’ aromas associated with sulfur (rotten eggs, burned rubber, etc). Chenin (like syrah) is particularly prone to it, resulting in aromas like a certain cheesiness or maybe even what Bettane called sauerkraut. But chemically this reduction is terrifically protective. This is why, Rigourd said, it’s a great grape to work with naturally, with no or little SO2—it can protect itself. But this reduction might be one reason chenin on slate can get a bad rap. He said, “People don’t know how to differentiate reductive characters from added sulfuric compounds, from minerality to varietal.” He cautions that when it comes to natural chenin, not to judge too quickly whether you like it or not, and be sure especially with a natural wine to give it a lot of air, allowing it to resolve with the oxygen.

Botrytis: Sure Vouvray (on the limestone) has botrytis but it’s mainly only found in the sweet wines. It’s not like on the slate in the Anjou, where it’s a constant issue. That slate promotes humidity which, combined with that soil’s heat retaining properties, leads to more botrytis pressure. So in wines from that soil, a little bit of that desiccation and sweetening is a pretty common issue. For a lot of people it diminishes purity. “Oh, it’s got some botrytis,” and up goes the nose in a sneer.

“People shouldn’t be so closed minded,” Rigourd said. “It is part of the DNA in the Anjou Noir.” A lot of people also confuse the honey and straw from botrytis with oxidation. Why this tradition of allowing the botrytis to happen? “We were not rich,” Patrick said, “So people harvested everything, including the grapes with botrytis. Making dry wine without botrytis is a very new fashion.”

Slate and clay in Ben Courault’s vineyard.

So, where are you in the debate? Try picking up a couple of whites from Saumur and taste them next to a bottle from Eric Morgat in Savennières and Didier Chaffardon’s La Mentule Matagrabolisée from the Anjou Noir, both in this month’s recommendations, and let me know what you think.

Additional reporting by Pascaline Lepeltier.