There’s the evidence of Anjou Noir and Anjou Blanc, limestone and schist in the Chateau d’Angers.

I never thought about the different soil types of the Anjou until a recent diatribe by the French wine critic Michel Bettane entitled “The Tragedy of Chenin.” Sure, I’ve heard tell that dry chenin blanc grown on limestone was described as a pure, bright expression of high acid and “minerality,” and chenin on schist as a more austere, powerful, bitter “intellectual” wine. But Bettane went several steps beyond and likened chenin on schist to, “stale choucroute, old cheese rind, rancid butter, moldy dough.” Rancid and moldy? Up went the blood pressure.

Instead of getting angry, I decided to get informed.Trying to get to the bottom of it turned out to be more complex than just “black and white.” Underneath the layers were issues of of tradition, desire, dirt and reality.

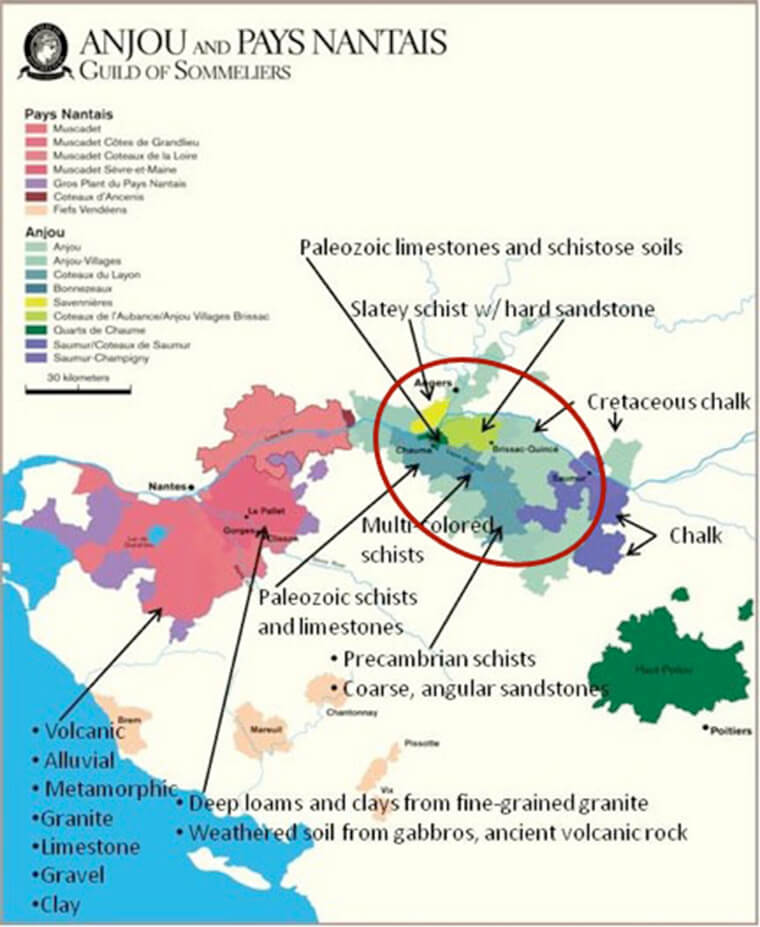

But first a little background. The Anjou region which hugs the town of Angers is made up of two distinct soil types. Anjou Blanc is simple: that’s largely the kind of limestone in Saumur and Saumur Champigny. Anjou Noir, which includes the sub regions Bonnezeau and Layon, has blacker soils of decomposed metamorphic rock, mostly schist. There is sandstone schist called Brioverian. That’s a mongrel containing plenty of quartz, mica, and feldspar. There’s also volcanic soils of reddish oxidized schist and greenish rhyolite, prevalent in Savennières.

Plunk a little volcanic into the map of the anjou and you get the idea.

Historically, the Noir was famed for its sweet wines, and yes, even Savennières was a sweet spot. But the dry chenin of today, (as a strong movment) is only two decades old or so. According to Jo Pithon of Pithon-Paillé (who makes both sweet and dry wines), the schist wasn’t the only factor to help create les vins liquoreux. Another factor was situational and climate. “We have more humidity in the mornings (helped by the two rivers that run through the land) allowing for botrytis,” he said. While good news for the sweet styles, when going dry, the winemakers need to keep an eye on the sugar level and not harvest when it’s too high.

But the most contentious point from Bettane was the issue of malolactic fermentation. He seems to view this as a choice, but in the hands-off practice of the naturalists, if the wines want to go through malo, the wines go through malo. In the Noir, they usually do. In the Blanc, they mostly don’t. Chenin without malo is angular. Chenin with it is more lush.

Kenji Hodgson who makes wine around Faye d’Anjou, the little area once known exclusively for its sweet wines, wrote to me his thoughts on the malo subject. “The Saumur whites don’t go through the malo. This is possibly because of the cold cellar temperatures of the troglodyte caves inhibit it.” Another reason is that limestone soils are lower in pH, higher in acid and that can be inhospitable to malolactic bacteria. Then he posited that perhaps some of the Saumurois actually choose to block the malo (with SO2 of course) in order to give the wines the impression of minerality and tension. This is something natural winemakers in the area (among them Patrick Baudoin, Mark Angeli, Benoît Courault, René Mosse, Richard Leroy) would never do. “So,” he said, “we are left with a softer acidity (lactic) rather than a tangier one, or mineral or tension or whatever you might call it.”

So, in the end is it Bettane’s preference for an angular wine that got him so angry at the schisistic dry chenin? Or is he just a staunch traditionalist who wants the wines of that area to stay sweet. Whatever the reason, I remain grateful for him opening up the door. The more research I did, the more controversial this whole issue became. Stay tuned for part #2.