Issue No. 01 October 2012

The Wine Recommendations

Domaine Julien Sunier

2011 Morgon

| Where | Morgon, Beaujolais, Burgundy, France |

| Grape | Gamay |

| Ag | Conversion to Organic |

| SO2 | Low |

| Price | $25 |

Domaine de La Grand’Cour

2011 Clos de la Grand Cour Vieilles Vignes

| Where | Fleurie, Beaujolais, Burgundy, France |

| Grape | Gamay |

| Ag | Certified Organic |

| SO2 | Low |

| Price | $25 |

Bernard Vallette

2010 Beaujolais

| Where | Beaujolais, Burgundy, France |

| Grape | Gamay |

| Ag | Organic; Certified Biodynamic |

| SO2 | Above 20ppm |

| Price | $19 |

Paul-Henri Thillardon

2010 Chénas “Les Boccards”

| Where | Chénas, Beaujolais, Burgundy, France |

| Grape | Gamay |

| Ag | Organic |

| SO2 | Lowish |

| Price | $30 |

Domaine Maupertuis

2011 Les Pierres Noires

| Where | Auvergne, Loire Valley, France |

| Grape | Gamay |

| Ag | Practicing Organic |

| SO2 | None |

| Price | $20 |

Domaine Dupasquier

2009 Gamay

| Where | Savoie, France |

| Grape | Gamay |

| Ag | Organic, non-certified |

| SO2 | At bottling |

| Price | N/A |

Mikaël Bouges

2011 Les Cots Hauts

| Where | Touraine, Loire Valley, France |

| Grape | Côt |

| Ag | Organic |

| SO2 | Pas de trop |

| Price | $15 |

Domaine de Montrieux

2011 Le Verre Des Poètes

| Where | Coteaux-du-Vendômois, Loire Valley, France |

| Grape | Pineau d’Aunis |

| Ag | Organic |

| SO2 | None |

| Price | $30 |

Nicolas Gonin

2010 Persan

| Where | Balmes Dauphinoises, Savoie, France |

| Grape | Persan |

| Ag | Organic, non-certified |

| SO2 | Low |

| Price | $22 |

Domaine des Dimanches

2007 Aspiran "G"

| Where | Aspiran, Languedoc, France |

| Grape | Grenache |

| Ag | Organic |

| SO2 | None |

| Price | $22 |

Domaine des Dimanches

2009 Aspiran "CMC"

| Where | Aspiran, Languedoc |

| Grape | Cinsault, Mourvedre, Carignan |

| Ag | Organic |

| SO2 | None |

| Price | $20 |

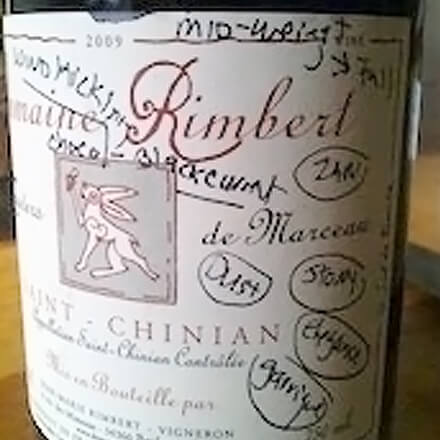

Domaine Rimbert

2009/2011 Les Travers de Marceau

| Where | Saint-Chinian, Languedoc-Roussillon, France |

| Grape | Mouvedre, Syrah, Carignan, Cinsault |

| Ag | Sustainable |

| SO2 | Low |

| Price | $16 |

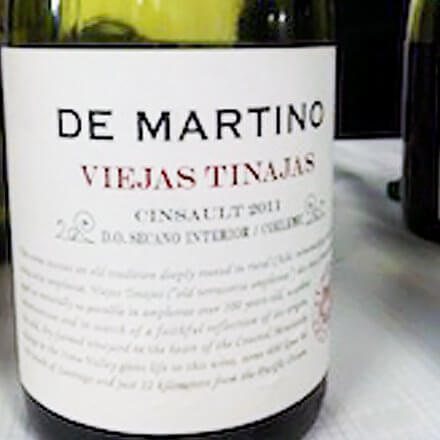

De Martino

2011 Viejas Tinajas

| Where | Itata Valley, Chile |

| Grape | Cinsault |

| Ag | Organic |

| SO2 | At bottling |

| Price | $15 |

Pheasants Tears

2011 Tavkveri

| Where | Kakheti, Georgia |

| Grape | Tavkveri |

| Ag | Organic |

| SO2 | Low |

| Price | $22 |

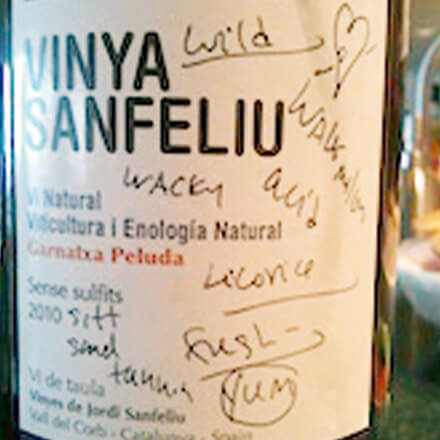

Vinya Sanfeliu

2010 Tinto

| Where | Tarragona, Catalonia, Spain |

| Grape | Garnacha Peluda |

| Ag | Organic |

| SO2 | None |

| Price | $25 |

Mikaël Bouges

2011 Pente de Chavigny

| Where | Touraine, Loire Valley, France |

| Grape | Sauvignon |

| Ag | Organic |

| SO2 | Low |

| Price | $15 |

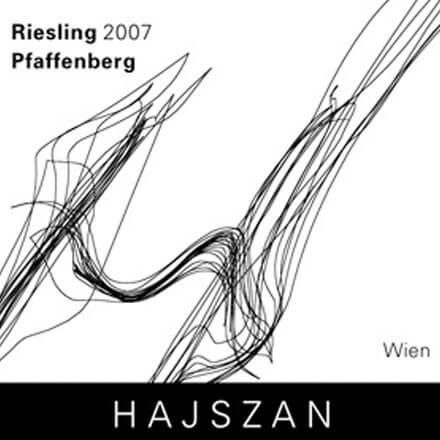

Weinbau Hajszan

2007 Pfaffenberg

| Where | Wachau, Austria |

| Grape | Riesling |

| Ag | Biodynamic |

| SO2 | More than usual for us |

| Price | $32 |

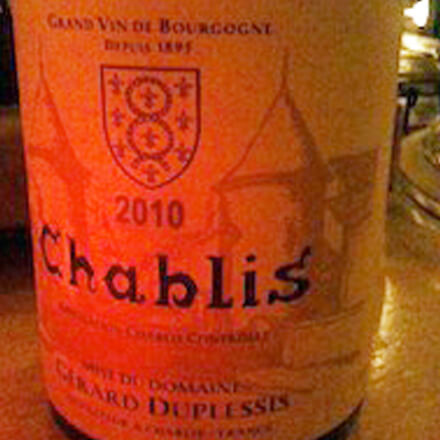

Domaine Gérard Duplessis

2010 Chablis

| Where | Chablis, Burgundy, France |

| Grape | Chardonnay |

| Ag | Organic Pending |

| SO2 | A little higher than usual for here |

| Price | $25 |

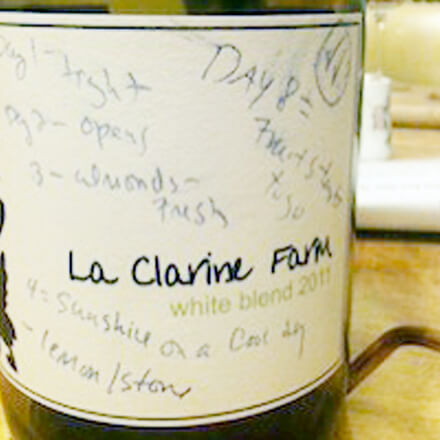

La Clarine Farm

2011 White Blend

| Where | Sierra Foothills, California |

| Grape | Semillon, Viognier, Marsanne |

| Ag | Sustainable |

| SO2 | At bottling |

| Price | $22 |

Where To Eat & Drink

In London

Higher Ed

A Word on Terroir and Granite

Profiles

A Trip to the Beaujolais

Two in the Beaujo

Greater than my love for Burgundy is my love for Beaujolais. Yes, I know this could be viewed as heresy and the Dukes of Burgundy might have guillotined me for it. But is it any wonder? With my affinity for the underdog and for gamay kissing granite soils it makes sense. No?

So this August when I was visiting the Wasserman-Hone household above Savigny and Russell suggested we head to Beaujolais for an old-fashioned lunch, and visits, I had no hesitation. I have at least a dozen winemakers there on my must-visit list, so I quickly booked a visit with two of them.

Domaine de la Grand’Cour

The drive from Savigny is a mere hour plus change, and Russell navigated brilliantly. Our first stop was Jean Louis Dutraive’s Domaine de la Grand’Cour in Fleurie. Dutraive worked with his father from 1977 but took over the domaine in 1989. For a while, the wines had been earning dubious reviews from both Mr. Parker and David Schildknecht. But in all fairness, perhaps the Wine Advocate hadn’t been aware of a dramatic change. Dutraive has been certified by ECOCERT since 2009 and that was also his first year of working differently. I asked him why he changed, after all, with due respect, he’s not exactly a spring chicken, and at this point in life, most people have settled into their work philosophy. “I tasted other wines that had more life in them, and so I started to work more naturally.”

Dutraive returned to full carbonic fermentation (dump whole grape clusters into a vat, seal it up, add CO2, and let the fermentation start from within the berry), uses a combination of stainless, old big barrels and small barriques of various ages, bottling unfiltered with minimal SO2 added (sometimes none at all). Vines have an average age of around 40–50 years, with a good chunk around 70 years old, moderately old for the region. He has about 9 hectares, the majority is on the granitic soils of Fleurie, in Le Clos, right near his winery. The others, are in two small parcels. There is an additional 1.6 hectares in Brouilly chalk.

Driving thorough Le Clos, Russell and I reached Dutraive’s run-down farm buildings. An eager dog came yapping at us. A quick peek into the weary vines (rot, uneven maturity), proved a little depressing. Working organically in 2012 was difficult for those who lacked commitment. Just the day before I had read dire predictions: 50% of the Beaujolais vignerons would be going under because of the difficult weather and low yields. But I believe those unfortunates are mostly those with little reputation for quality. Even though the region, with serious winemakers like Dutraive, is on the upswing Beaujolais still has plenty of underachieving vineyards and winemakers.

Clos, Dutraive told me that he’ll be down to 15 Hl per hectare. He shrugged it off. This is what he signed up for with organic, it is what he signed up for in dealing with agriculture. He might not have much to sell in 2012, but he has enough 2011, there’s always 2013, and he’s a vigneron with a reputation on the ascent.

With the dog running shotgun, Dutraive brought us through the large vat room, lined with barrels, ovals and barriques. We sat down at a rough hewn table and commenced.

Clos du Grand’Cour is from younger vines (10 years). This has a touch of sulfur (2mg). Structured and silty, touch of blood orange. This is the easiest cuvée to find in the states as it’s imported and distributed by Polaner Selections. If Polaner doesn’t jump on the others fast, he’s going to lose out.

For me, the heartthrob wine came from older vines. This, a no-sulfur-added bottling of Chapelle les Bois, was raised in the big foudre. It had a slightly gritty texture, a powder and touch of cinnamon aroma and mouthwatering acidity. It spelled place.

The Cuvée Champagne Vielles Vignes is from very granitic soils. The structure shines. It also takes a little new wood which seemed integrated to me.

The Brouilly Vielles Vignes comes from very different soils of clay and chalk, the texture was denser, lots of savory/fruit balance of clay and chalk.

Three days open, they still held together. The prices are between $20–27.

After a strange Beaujolais blanc raised in acacia while tête de veau was devoured all around us, we took off in search of pink-cheeked Julien Sunier.

Domaine Julien Sunier

Turns out Sunier lives in a piece of Vermont-like paradise of Beaujolais in the village of Avenas, 750 meters above sea level. It’s a mere 15-minute drive from his three plots of land en fermage (he leases) in Régnié, Brouilly and Morgon.

As a guy born in the Côte de Nuits, he made a provocative decision to cast his lot with gamay. After all, as the son of hairdressers from the Côte de Nuits city of Dijon, a few kilometers from Marsannay, you’d think pinot would be in the blood. No?

Fate took its course. He met Chambolle winemaker Christophe Roumier through his parents’ salon. Sunier spent time at Roumier’s domaine, he seriously caught the wine bug and went down the New World road. His apprenticeships took him to New Zealand and California. This made him an attractive hire for the now very modern Momessin’s Clos du Tart. “I was given a bonus for every point over 90,” he confessed to me. But he also fell in with Nicky Potel and long biodynamic winemaker, Jean Claude Rateau. He took the left turn towards organic, low sulfur and natural wines. He snagged himself an ancient vertical press in the Côte d’Or, found an old barn, built his winery.

Sunier works with only about 15ppm sulfur but as he’s not so accepting of what the trained world considers flaws, he polices the wines with obsessive laboratory checks to guard off the sheepiness that brettanomyces can give as well as the sharpness of volatility. “I hate them.”

His Régnié is grown on granite and sand and it was hard, a little diffuse yet perfumed. The Fleurie plot stands at 480 meters near the La Madone vineyard. The wine was shy but had a great line of nervous tension beneath the sips. The Morgon was stunning, quaffable, and no obvious carbonic character other than its ethereal nature, a pretty whisper. All should put on weight as they age over the next few years. I suspect these need some laying down for their character to pop. Not much, a year or two.

“I want an easy wine you can drink every day,” he said. In other words, he has come a long way from Clos de Tart. In fact, I think he suffers from reaction formation and it’s not a bad thing at all.

Sunier loaded us up with some eggs from his hens and a few tomatoes from the garden and we drove north towards Beaune and dinner.

Profiles

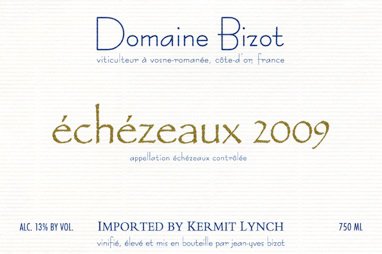

Jean Yves Bizot in Vosne-Romanée

The last time I was in Vosne at this house, down the block from the church, I was visiting a winemaker from the Hautes-Côtes, Claire Naudin. Charmed with her wine, I swore I’d be back to visit with her husband and see how he worked. And so this past August when most of France was on holiday, I waited in the Naudin-Bizot courtyard. Jean Yves Bizot soon emerged from his house, and the vigneron, tall and lanky like an overgrown Harry Potter, lead me to his nearest vineyard. He pulled back a vine and tucked it around a wire, “Can you tell how fed up I am with them this year?”

We were just west of the road that used to be the RN 74 in his Les Jachées, a village level vineyard. Our plan was to visit, taste and take dinner with his like-minded vigneronne wife. But first, a moment of silence. All around us in his and other vineyards were the signs of the 2012 Burgundian summer of ten plagues. Cold. Hot. Hail. Rain. Mildew. Rot. Frogs. Slime. Boils. More Rot. It was hell if you worked organically, which is Bizot’s way, though his vines are not certified.

Yes. I could tell.

Jean Yves studied Geology. When no one in his family wanted to take over the family vines, he stepped in. The year was 1993 and his first vintage was in 1995. “I had to unlearn everything I was taught in the viticole,” he said to me when I first met him, over eggplant curry in his kitchen. He said his transformation to minimalist winemaker started slowly. “I asked myself what was absolutely necessary to make wine.”

He began to strip the tools and ingredients away, one by one. He found out the only thing he needed was a container to hold the grapes, his feet for pigeage and barrels to put the wine in. Along the way, he realized that he couldn’t tolerate sulfur. He reduced his usage until there was sometimes none at all. “Do you know there was very little sulfur used before the 70s in Burgundy?” he asked me.

His first vintage without sulfur was 1998. Besides the lid sulfur puts on the wine, he also speculated that it also increases the extraction. “And you know that black currant in pinot?” he asked. He said that is mercaptan, a wine flaw usually characterized by a cabbage-like smell and, yes, he also attributes that to the effect sulfur can have on a wine.

He raises his wines, no matter which terroir, in 100% new oak, a choice which scared me. His reasoning is that with new oak he can avoid sulfuring barrels before usage. My first wine of his, over that eggplant, was a 2007 Hautes-Côtes white. I found it overpowered by wood vanillas, but still there was an intriguing wine beneath. It was impossible to be indifferent about it.

The domaine is tiny. He started out with 2.5 hectares split among fragmented parcels in Vosne and Échézeaux. He recently added an extra hectare in three parcels of old vine acquisitions: south of Dijon, Bourgogne Le Chapitre and Marsannay Clos du Roy.

Down though a Palentine blue door, into a typical shallow ancient cellar weeping moisture, we tasted a few of his 2011s. In this infancy, depending on the terroir, they handled the oak differently. The Marsannay Clos du Roy, from a dry and hot terroir, had the hardest time integrating the oak. I was deeply impressed however by the cooler parcels. The Vosne Les Jachées (the parcel he was peeved with earlier in the evening) had such vibrancy. The Echézeau Grand Cru was more angular.

Much is made of his having lived down the block from the late God-like winemaker Henri Jayer, a relationship that was formally deified in The Drops of God, the fabulous Japanese manga. It’s practically apocryphal. Writers have penned that Jayer was Jean Yves’ mentor. Robert Parker’s ex-Burgundy critic Pierre-Antoine Rovani was responsible for much of this. I asked what the truth was and he answered, “I said to Pierre-Antoine, many years ago now, that I learned more about wine speaking with Jayer in three hours than two years of study of oenology. He somehow concluded I was a disciple of Jayer. I think it’s a little bit shortsighted. My home is less than 100 meters up from his house. We sometimes discussed wines.”

He believes Jayer had a lot to teach him about how the job doesn’t stop when the wine is made, that marketing is important. But he continued, “Our ways to make wine are quite opposite. Consider his position on the stems (Jean Yves uses 100% stems. Jayer destemmed.) or the cold maceration (Jean Yves uses none, while it was Jayer’s calling card). But the main lesson—and the most important—I received from him is to free myself from the common and usual rules to make wine. In his era, he imagined another solution, completely different from what other producers were doing. So, in this meaning, yes, I agree, I am a disciple of Jayer. We find our own solutions to problems.”

The Advocate is responsible for another piece of parroted misinformation. Parker, in his first coverage of the 1993 vintage, wrote that Bizot made his wine without sulfur and without fining or filtering because of his agent, Patrick Lesec. This is not true. The impetus was all Bizot. The winemaker is certainly a good listener, but he has a strong will of his own and is not a style chaser.

Inside, Claire was making quiche with curried crust, the boys were watching Buster Keaton and more wines were waiting.

2010 Vosne Romanée VV

Satisfying, savory and peppery, a long powerful mouthful. Royal stuff—scratchy, classic smoky tannin. High-toned and very changeable, lively with some cherry and spice and animal (Pricing around $125).

2010 Bourgogne Rouge Chapitre

Reduced on nose, not in mouth. Blows off into a pretty little burgundy. This is crazy price for an ordinary Bourogne Rouge, but far from ordinary (Under $87).

1999 Vosne 1er Cru

Absolutely beautiful. I can’t thank him enough for opening this wine. Gorgeous. Velvet. Complex nose of spice and clay and a touch of eucalyptus which kept this warm vintage fresh. A lush, generous wine with a kicky, silty finish. Unless you can find this in auction, it’s not available. The 2010 will sell for around $240.

Pricing: General 2009 prices went from $67 for his Hautes-Côtes, to $331 for the stunning Échézeaux.

Even with the star status bestowed on him by The Drops of God, Jean Yves doesn’t get a lot of press. This might be due to some breathtaking prices. But, an interesting man? Absolutely. Should you buy? If you have the money and the curiosity? Absolutely. Anyway, I’m a sucker for 100% stem vinification.

Remember to give it some age. Give that oak a chance to meld, and the stems to do their magic trick. Not sure if you should wait for your grandchildren but ten years should pay you back royally.

Importer: Kermit Lynch