I am so happy to publish our winning essay for The Feiring Line Writing Mentorship Award. Out of our 80 submissions, Meg Bernhard’s piece, “Making Wine With A Woman” captured the votes from our wonderful judges, Amy Bloom, Ray Isle, Talia Baiocchi, Christine Muhlke and Adam Sachs.

Based in Spain, Meg is a working journalist. Her work has appeared in The Los Angeles Times, Harper’s Magazine, and Guernica, among others. A journalist on the rise, she is relatively new to the subject of wine. We loved the way she delivered the sensual in the story, the arc and nuance. In addition, working with her on the edit was a joy. I hope you’ll be reading more from her in these pages and other venues.

by Meg Bernhard

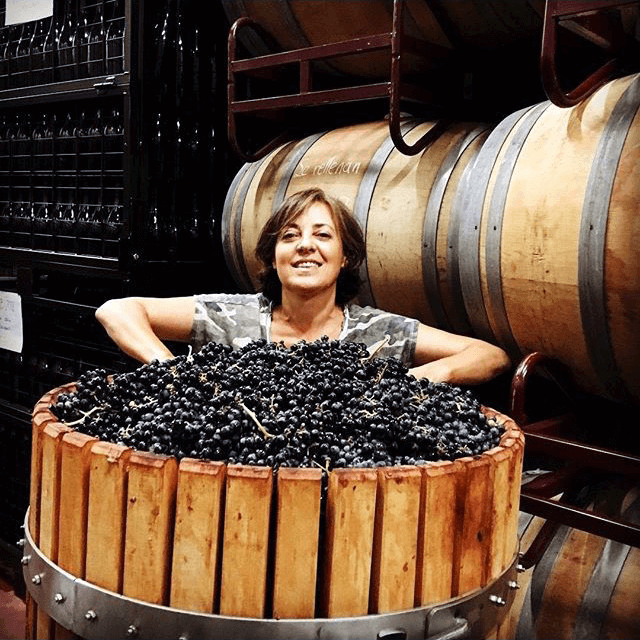

On a crisp November morning, Carmen López Delgado, 4’11 and wrapped in a thick camel coat, waited for me on the train platform. Her hair was curled and brown with golden streaks, and her lips were deep burgundy. She looked regal. She welcomed me with a long hug, as though we had known each other for years.

It was the fall of 2017, and I had moved to Castilla-La Mancha, in Spain, to work in Carmen’s winery. The month before, I had sent her an email asking if I could volunteer on her vineyard; she had responded promptly with an invitation to live in her home.

I had graduated in May and traveled to Spain with a grant to learn something new and unrelated to my history major: how to make wine. When I was in college, wine came in boxes or two-liter bottles made for getting drunk fast.The stuff was bitter, or astringent or overly-sweet. It gave me headaches. I started to avoid drinking. I made an exception for small, conversation intense gatherings in dorm rooms. We drank from coffee mugs.

The evening after I arrived, Carmen’s husband drove us to a dingy bar just off the highway. In the fading light, I could see miles of vineyards, their vines gnarled and naked. We sat by a candy dispenser in the back of the bar as we waited for a few friends to arrive. There were Javi and Merce, Carmen’s friends from elementary school, and Javier and Alicia, friends of Merce’s. They were all three decades older than me.

Friday nights at the bar became my classroom. Carmen would uncork three or four bottles, sometimes her own wine — strong, liquory gracianos and tempranillos meant for the wintertime — or wine from friends in Catalonia and Córdoba and Galicia and Alsace, places that seemed a world away to me. The wine could help me imagine these places. “Terroir,” Carmen told me, “means that the wine should reveal something essential about where it comes from.” A briny Malvasia de Sitges would take me to a vineyard by the Mediterranean. An albariño would take me to the lush, steep canyons of Galicia.

We ate, we always ate: cured meats and cheese, or patatas bravas, or tortillas de patatas. Carmen would pass around glasses she had brought from home (the owner of the bar was a childhood friend who permitted this sort of thing) and lead us through a tasting. She would tell us to hold the glass up to the light to examine the wine’s color — “Look how purple this is,” she’d say, “like a queen’s robes.” Then, we would bring our nose to the glass and offer words to describe what we smelled: flowers, berries, cedar, orange peel. “Smell is the human sense most strongly associated with memory,” Carmen would say. What we smelled in wine was deeply personal. She quizzed me on what I smelled and I, hailing from a California suburb devoid of strong sensory details, tried to find the few familiar aromas I had long before tucked away in my memory.

“This,” Carmen said one night as she put her nose to a glass of her own 2017 graciano, aged in oak, “smells like chicken blood, just like when my mother used to cut off hens’ heads and drain their blood into a bucket.” We laughed, shook our heads. We did not smell the blood.

The last step was to drink. Carmen closed her eyes when she did this, and when she liked a wine she smiled with her whole face. “This one makes me happy,” she would say. Another would surprise her, tickle her. From her, I learned, wines should make you feel something — nostalgia or homesickness or delight or passion. Wines that provoked an emotional response made the best sort of conversation. The worst review a wine could receive was silence at the table afterward.

The wines we drank always started conversation. We talked about everything we could think of that winter: childhood memories, the Spanish Civil War, the Catalan independence movement, which had been intensifying since October. Carmen’s wines often led to a discussion of Castilla-La Mancha. They reminded her friends of wines their grandparents had made from vines in the neighborhood.

One of these nights when we had drunk glass after glass of a rich tempranillo, Merce brought Carmen, Alicia, and me outside for a smoke and told us about the most famous bullfighter of Santa Olalla, Gregorio Sánchez, who once killed six bulls in 80 minutes. “His portrait’s on the wall of every bar in the province,” Merce said, taking a long drag on her cigarette.

We leaned against the wall of the bar as the three women shared the cigarette, the smoke they exhaled mixing with my cold breath. I clutched the stem of my wineglass and felt my nose turn red from the freezing air. The women laughed and sipped and talked about the things that were on their minds. Their husbands didn’t cook or clean, their sons were using the phrase “feminazis.” Their lips were purple from the wine and the cold and their voices were loud and certain and firm, blending together until it seemed to me just one voice was speaking.

Sometimes, when we had no work to do, we sat at the kitchen table and Carmen told me stories of her past. She had been a stay-at-home mom when she became sick with cancer. There are no pictures from this time, when she didn’t have hair — a conscious attempt at forgetting.

She says the land in Santa Olalla saved her. In 2005, while still sick, she bought the 14 hectares, scattered with olive trees, from her mother, and planted the vineyard. The land, of clay and chalk, saw scarce precipitation and had an extreme climate. Yet the vineyard made her feel at peace. She found the work invigorating. It gave her the energy to focus on recovery.

In February, we spent long days in the vineyard. It was pruning season, and there were two of us, sometimes three, to chop branches from thirty thousand plants. The earth was frozen. The sky was concrete gray. A terrible wind blew. On my first day, Carmen taught me how to prune a plant so it would be strong enough to hold healthy grapes. “You have to learn to read the plant,” she said. “You need to know where it should grow next year.”

We worked and my palms ached and the sound, the abrupt crack as the shears met the wood and the wood fell away, echoed in my head. Carmen’s mother collected the branches as we went. My hands were clumsy, and I worked slowly, making mistakes. Carmen corrected me. But after hours of walking up and down the rows, I fell into a rhythm. The work was mesmerizing. I thought of the power I wielded in dictating how the vines would grow. The moment I cut a branch, my action was irreversible. The gravity of this realization, that I could radically change the future of a plant — and, in turn, the harvest — drew me into a sort of tunnel vision. I saw nothing but the vine in front of me.

Sometimes Carmen would pause and comment on a single vine, beckoning me back to the present. “They remind me of humans. Human hands,” she said. “Just look at them. It’s like they’re grasping up into the air.”

I left Carmen’s house in the springtime, eager to continue working outdoors. I wanted more experience in the vineyard — pruning, fertilizing, planting, grafting — so I moved on to Catalonia.

I did find work, but winemakers were unwilling to let me do technical tasks, telling me I was inexperienced. When I dug holes for recently-grafted vines, male workers teased me for my technique. When I wanted to prune, I was asked to collect fallen branches. My face burned red in embarrassment, but I didn’t speak up.

I sensed a holdover from a time when women were blocked from the winemaking process. Back then, as recently as half a century ago, some men thought menstruation would spoil fermenting wine, so women were barred from the cellar. Men thought women’s frail bodies would not exert the proper amount of force to extract juice, so they were prohibited from stomping on grapes. Instead, when men were finished with the day’s work, women would make them lunch.

In late August, when the grapes were ready, I returned to Castilla-La Mancha. We were up before the sun, rubbing sleep from our eyes as the car sped to the vineyard in Santa Olalla. The morning sky changed from black to deep blue to a soft violet, then pink, and I gazed out the window, watching the gently rolling hills spread out before us in all directions. In the vineyard, we were surrounded by a sea of leafy grape vines. A star faded in the sky. Carmen handed out gloves and shears.

“Listen,” Carmen said to the group of workers gathered around her. There were sixteen of us: Carmen’s children, friends, and contract workers from around the province. “Don’t cut anything dehydrated, or any of the small bunches high up. And no leaves. Please, no leaves.”

We inched along the rows of grape vines. Our hands were machines clutching deep purple bunches, searching for the stem, slicing the grapes from the vine, tossing the grapes into crates. A tractor whirred. Harvesters traded jokes. Shears chopped and cracked wood. Every once in a while, I looked up to watch the men working. Sometimes they cut unripe bunches, or forgot ripe grapes, or cut too close to the vine, vines that I had spent those long February days working to shape. Their carelessness pained me. I wanted to yell out across the vines, to warn them that their negligence could permanently damage the plants. But I kept my concerns to myself. I watched Carmen watching them, her sharp eyes missing nothing.

The sun blazed on the back of my neck, and my shirt dampened with perspiration. By the end of the day, we had collected 20,000 pounds of grapes. My arms were limp, my back sore.

After we finished, I peeled my gloves from my clammy hands. A man, his face shaded by a wide-brimmed straw hat, approached me, twirling his shears. “You’re the American, right? What do you think of this work?”

I liked it, I told him. “It’s really hard, but I’m happy to do it. I’m learning so much.”

“You girls work slower than everyone else,” he said. “The guys are just faster, but that’s okay, that’s normal. You girls are thorough.”

I glanced at Carmen, wondering if she’d heard. She was standing a few meters away examining a row of vines.

Carmen frowned, picked a bunch of grapes from the vine, and held them up. “Come over here,” she yelled to the man next to me. “Your guys missed all of these grapes.” He opened his mouth to yell back, but said nothing and trudged over with three men to finish collecting what they’d missed.

Carmen supervised the men as they worked, correcting their mistakes. As she walked down the row, some of the grape vines reached her neck. A few towered over her head. I hardly noticed, because in that moment she seemed taller than everything, taller than the grape vines and olive trees and the telephone wires in the distance. Taller than the men, too.

Comments are closed.