Spirits were high at the café table outside of the now defunct Bar Stella in Verona. It was about two in the morning, when any normal person would be drinking angular white wines or even better, the fizzy stuff. But not this night—a bottle of the 1996 Barbacarlo was what appeared. The label was impeccably old world and the wine grabbed me. It was tannic, rustic and volatile. Pure old Italy, packed with charm. Made by Lino Maga. I had never heard of him.

Best of TFL: A Maga Done Right

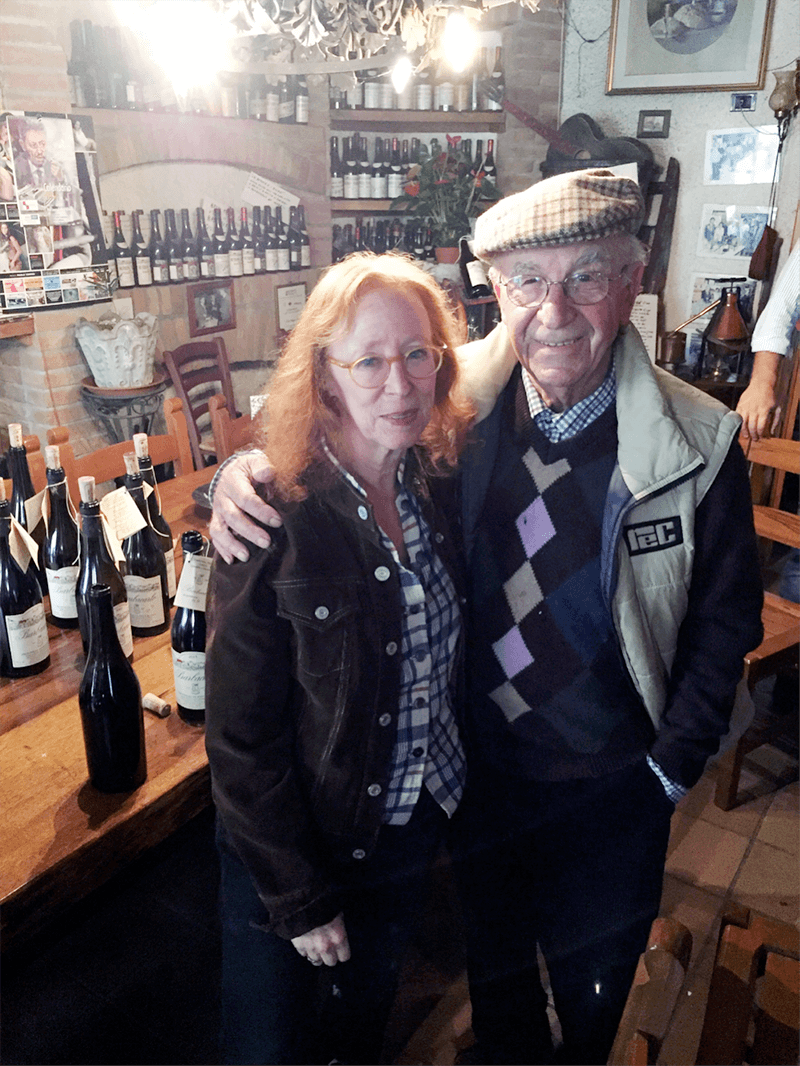

That’s why a year and a half later, when I was meeting Elena Pantaleoni of La Stoppa to explore Emilia and she suggested we make a short detour to visit Maga and the Barbacarlo, “Because to understand Emilia, that’s the place to start,” I said, sign me up.

Maga lacks the star status of Bartolo Mascarello, the rakishness of Lorenzo Accomasso, or the established sanity of Emidio Pepe, but he should be up there for those who seek out the most profound traditionalists. And there he is, ensconced in the Oltrepò Pavese region in Lombardy. Tucked into the northwest of Italy, south of the river Po, it’s a prime example of a fabulously destroyed region. If known for anything, it’s for their riesling and pinot noir. Pathetic. I mean, when was the last time you drank a bottle of wine from the Oltrepò?

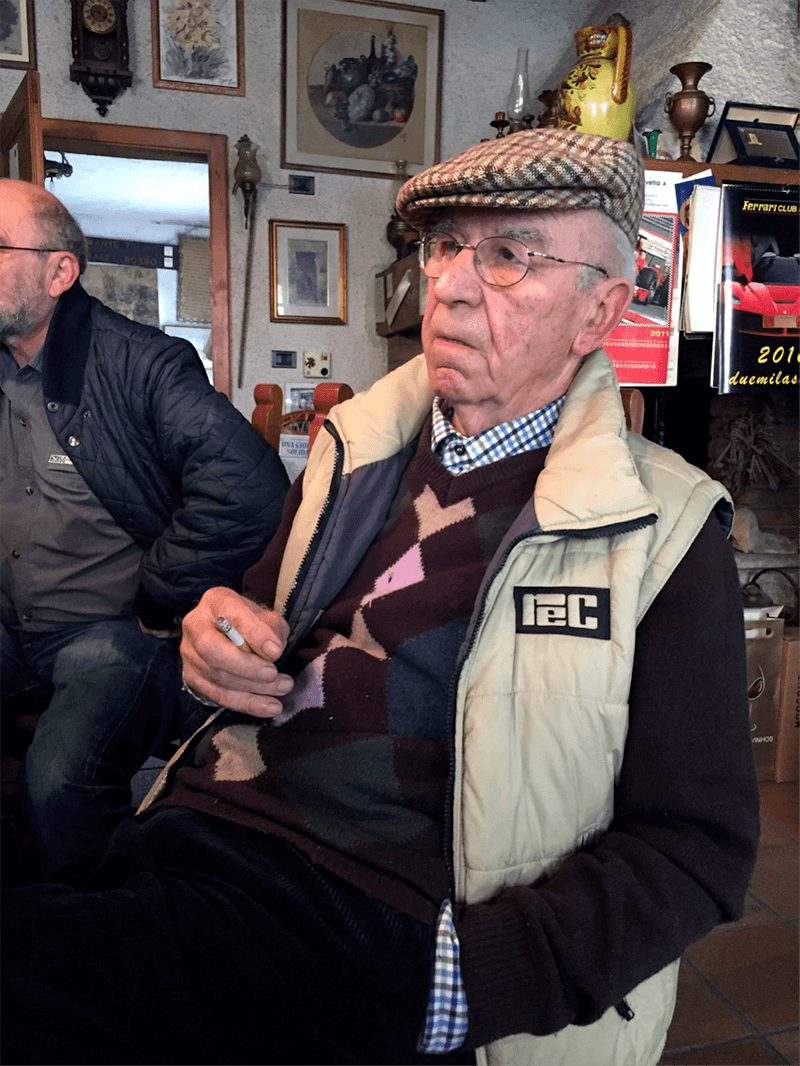

Elena picked me up at Malpensa and in under an hour later, we arrived to the town of Broni, where Maga receives guests and lives. His yard was filled with old equipment, almost like a wine museum. We parked under a majestic persimmon tree, heavy with not-quite-ripe fruit. We walked into the receiving room, littered with upright bottles, typewriters, meat slicers, knife blocks, all framing the long wooden table which could have seated over twenty. It had to have been the centerpiece for parties and serious tastings that stretched into the night. Now, it was mostly collecting bottles and books. The winemaker was wearing that standard issue old-Italian-man cap, mismatched plaids and argyles with a moth hole here and there. Between his fingers was the never-extinguished cigarette. Maga shook my hand, kissed Elena on the cheek. We sat down. He grabbed the 2015 Barbacarlo from the collection of open bottles in the middle of the table and proclaimed he had just finished his 80th vintage. He poured and brought the glass to his nose. First he sniffed with his left nostril then immediately switched to the right. I wondered, did he learn that from his old friend, the late and very great wine writer, Luigi Veronelli? Then took a slug. “Wine is a serious thing,” he commented. “It is food.”

Preach, I thought, and he did. “In Italy, government forgets the farmers. More people are working well today but the government is against us.” Satisfied with his sniffs, he passed the wine our way.

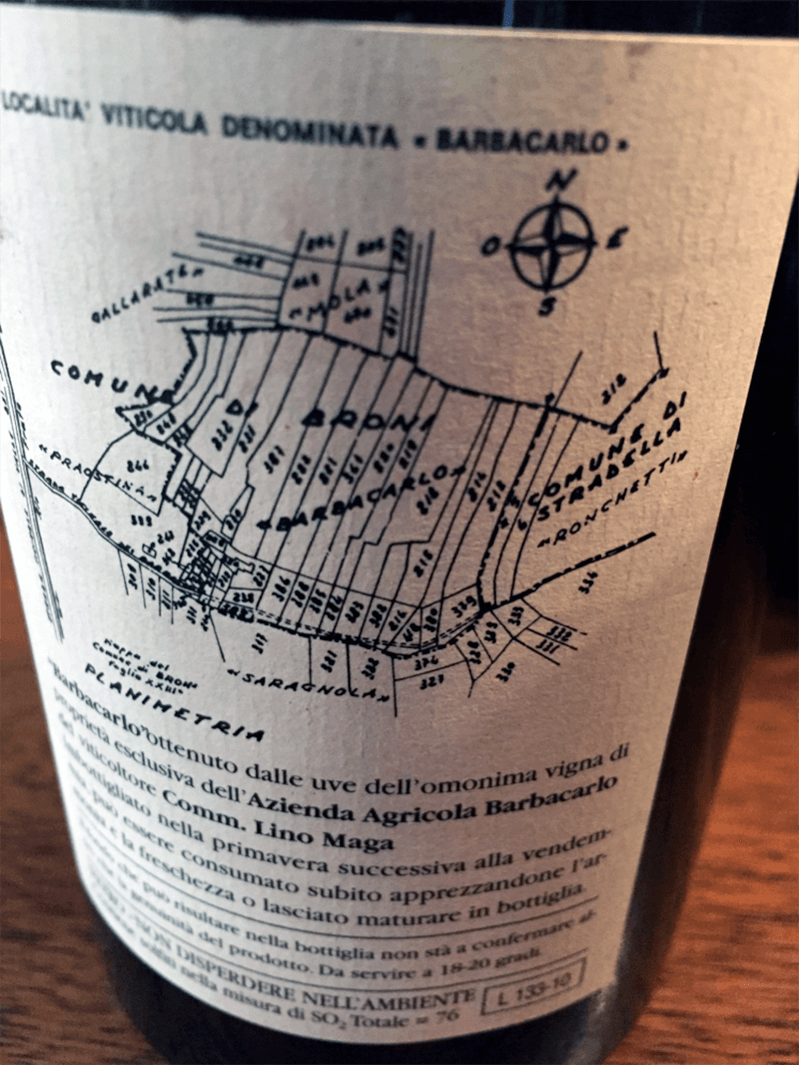

He spoke slowly. He was guarded, but stories started to flow. Maga left school when he was 13 to become a vignaoli, he told us in dialect. You could say that about his wines as well—the dialect part. His methods haven’t changed over the generations; viticulture is still organic. The grapes are destemmed, crushed, put into 3000L tini. There’s pigéage. He doesn’t use his press wine except to clean his tanks. Like many who make wine the same way as their ancestors, he watches the moon. “I rack during the old moon,” he said. “I do it about six or seven times, quite a bit to avoid filtering,” he added. Then he bottles early—the spring after vintage, and keeps the bottles for fifty days before he releases them. As of 2005, when the government insisted on labeling for sulfur, he began sulfuring. He lists the total content on the label, but in truth, the wine acts as if it has none.

I admit that the 2015 was not thrilling. It showed the difficult dry and hot vintage. Tannic as well as stuck with a good deal of residual sugar.

The 2016 Barbacarlo, however, was classic. Plenty of tannin and bubble but with enough stuffing to forgive it. Finally there was the Montebuono 2012 with a full throttle fizz. Who knows what it will be like when it finds its way. Bottling that early and then taking it to market that soon, anything can happen in a Maga wine.

In any event that fizzy wine was the opening for Maga to hold forth about the bubble wine history and the decline of Oltrepò Pavese. His attitude was one of derisive helplessness.

“There was a cooperative, Santa Maria,” he said in a deep voice. “They made spumante. It was a big success. After that, everyone planted grapes that didn’t belong in the area. Like pinot noir. In the 1980s they planted riesling.”

“Pinot grigio,” he said with disgust. “They all wanted spumante.”

To be fair, sparkling does have some history in the region: back to the 19th century Otrepò Pavese grapes provided others with a base for sparkling, so you couldn’t blame them for wanting to make their own. However, the newfangled grapes are more recent interlopers.

“But Broni was always known for black grapes,” he said, referring to croatina, vespolina (here called ughetta), uva rara with some barbera. “The warmth from the limo makes the area good for it.” To make his point he presented us with a chunk of rock, a heavy chunk of very messy, hardened sand, as if dragons’ teeth were embedded in it. It didn’t look like any limestone I had seen.

During the rush to bubbles, he was loyal to his red wine from his famed hill. He actually has two plots that he vinifies separately. Four hectares on Montebuono go into that wine. The other four are on the monopole Barbacarlo. And even though plenty of others fraudulently bottled their own wine as Barbacarlo, it was his family’s thing, named after a long dead uncle. ‘Barba’ in Pavese dialect means uncle. Carlo was the man’s name. Their hill is ‘Uncle Carlo’. He fought for twenty plus years to earn the unique right to use the name. It was awarded in 1983.

Having won battles, with his 80 vintages behind him, he acts as if he’ll live forever. Or rather that his precious hill will live on as his extension. He talked of replanting, as a young man would. The future.

But the whiff of anger and dejection clouded the room as Maga continued on with his story. Luigi Veronelli tried to champion the wines and had plenty of them in his private cellar even as the world forgot Broni and Maga. For decades there were few visitors. Then in the hot year of 2003 he failed to get the DOC, “The wine had more than 12 grams of sugar.” His response was to be an IGT. “I’m out of the law,” he said and blew smoke in my direction. “Does this bother you?” he asked, perhaps a bit slyly.

I suppose that was traditional, too. But I was in his home, not mine. He could do whatever he wanted with his cigarette. “I’ve made it this far with smoking, so there’s no need to stop.” He didn’t. And his son, who now has taken over the cantina and had slipped in after a nap, lit up as well.

And what about that vineyard that he fought for years to claim the right to its name? “Can we go to see it?”

“No, it is too steep.”

And as if to make the point that he wasn’t going anywhere, winemakers and importers came through the door. Pilgrims are coming to pay their respects, just as they do with the other greats, quick before he disappears.

Visiting the Barbacarlo

Elena and I stood under the persimmon tree, she had a cigarette. And we talked. I was dejected about not seeing that steep hill. That’s when a young woman in sweats came around to rev up her scooter. Elena had an idea. “Do you know the way to the vineyard?”

“Sì. Sì,” was the answer. We hit the ignition and followed her behind Broni, past the vines, and climbed up high. And higher. We arrived. I thought, this wasn’t steep, it was positively child’s play compared to some spots in Cornas, the Mosel, Ribera Sacra. And the planting, it was a crazy cross-hatch of exposures as if many different plots had been crammed into that one hilly vineyard. It’s as if I, with my crazy sense of organization, had been in charge. We walked to the top. The soil was parched white. “Elena,” I asked. “What is limo, it’s not limestone, right?”

She pulled out her iPhone dictionary and she showed it to me. “Silt?” This vineyard was loam and silt. I never took silt seriously and would realize in the coming weeks as I experienced the profound silt of Emilia, that I would need to update the Dirty Guide to fix that hole. It would become a theme over the next days. So, I looked over those vines with their roots in the silt. They showed the difficulty of the vintage and every grape that could be picked, had been. We trudged behind the girl who lead us on her moto. “There,” she pointed when we got to the top. She was indicating the hilltop across a deep valley, on the other side. It was only then I realized that we were standing in Montebuono. The slope on the other side held the vineyard we sought.

There it was. And sì, sì, Uncle Carlo was an impossibly steep slope. There were plenty of holes in the vine lines, from the wild boar, showing the need for replantation. There were the abandoned terraces from an attempt to rebuild them a decade or so ago. I could well imagine the kind of wine that could be made from there. Better than Maga is making today? Perhaps. But what still is squeezed out of that land is a wine that looks so far into the past, with its charms and difficulties, that it demands and commands respect. If you get a chance, the wine comes in at times to the country. The Montebuono might run about $50 or so. The Barbacarlo runs between $70–$120 or more, depending on vintage. Right now, unless it’s already been snapped up, Astor Wines has some items from Luigi Veronelli’s cellar. The 1979 Barbacarlo is one of them. Grab it if you can.