I came to caring about Jews and wine early in life but I came to Aszu, the great botrytized wine of Hungary late. I was working for VOS, trying to be a salesperson. I flunked. But I did get to know another aspect of wine, develop more knowledge that served me later, and learned to sneak into the fridge for a little afternoon delight. That would have been a hit of the Tokaji Victor imported. Acidity through the roof made this elixir palatable to me who prefers bitter to sweet.

But while I’ve never written about it—or visited Hungary, I’ve searched for a story about Jewish winemaking heritage. I sensed that there was one far more noble than the Manischewitz stereotype. I wanted to know about the Jewish vignerons who perished with World War II. I could find few leads. Last year a gentleman named Gerry Oster called me with the one.

This was shortly after his Washington, DC-based sister was planning a back-to-her-roots tour to Hungary with her husband. While looking over a website of places a tour guide would arrange for them to visit, her husband called out and said, “Honey, come here. Isn’t this your mother’s house in Mád?”

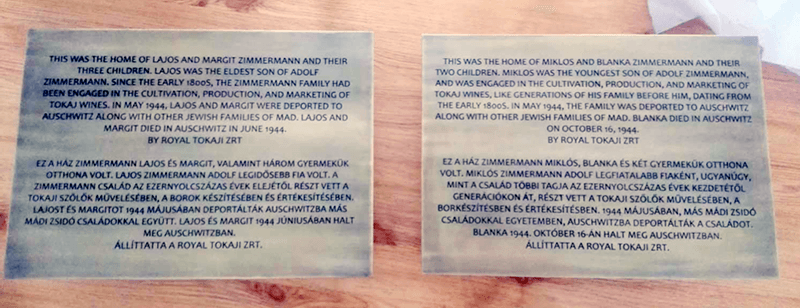

The house, now part of the current headquarters of Royal Tokaji winery, was the very same one that Susy Oster née Zsuzsanna Zimmermann was wrenched from as a young girl in 1944. The Forward ran a story. I yearned to go deeper into it, head to Hungary, find other leads, but with book pressures I just couldn’t manage. So, I waded into it from afar.

At one time 10 Jewish families owned 80 percent of Mád’s Tokaji industry. The Zimmermanns had been one of them and they were wealthy farmers in the vine-rich town of Mád. For at least three generations, their family had lived there and worked the land. They worked the land. They made wine. Some kosher. Some not. They also owned some of the best vineyards—termed “first growth,” and covetable cellars, nearly a mile long. Those were perfect—and rare—for aging the sweet wine for which the area was so famous. Mrs. Oster’s idyllic youth was full of memories of harvest and fermentation.

All ended with occupation. From there, her family was sent to the ghetto, then later to Auschwitz and a work camp for Siemans. She survived, liberated in 1945. Her mother did not.

After liberation she was taken in by a San Diego family as a war orphan. She learned to speak English with little accent. With communism in place, she lost all hope of reclaiming her family’s property. She had repudiated what she felt to be an insulting reparation offer from the government. Now a healthy woman a year or two away from 90, living near Los Angeles. She left that part of her life behind—until, that is, her children told her what her past home and land had become.

Partners Lord Jacob Rothschild and wine and garden writer (and hero) Hugh Johnson acquired Royal Tokaji. Damon de László came later. It debuted with the 1994 vintage and much fanfare. It was astonishing wine news. Tokaji! Back from behind the Iron Curtain to the drinking world! Johnson said in a 2015 interview to Somm Journal, “As a wine writer and lover, I would have gone to any lengths to taste wine that inspired Homer or Virgil. Why would I pine any less for the wine that Pushkin and Tolstoy drank, and that Peter and Catherine (both Great) considered one of the privileges of the tsars?”

But there was no mention of any connection to the Jews. Even as the company asserts history is a mainstay of their product, the Jewish piece vanished.

This was odd. It wasn’t as if it was a secret. Marguerite Thomas wrote about them in a piece she wrote in 2000. But in that article she wrote something that was not true. It remains a mystery how she came to understand that Hugh Johnson & Co. bought the estate from the Zimmermans themselves. Consequently that changed to the local church, but as the surviving Zimmermans never reclaimed their property the actual truth of how they came to own the property was never fully clear to the family. When Gerry’s sister and husband traveled to Royal Tokaji they were treated graciously. Everyone there knew who they were.

Having been privy to the email exchange between Oster and the partners, and one personal email where the Mr. Johnson expressed surprise about what took the family so long to come forward—I must admit something I was shocked at, though chalked up to ignorance—they came forward as soon as they understood that what they had built survived—I came away perplexed at what could have been seen as willful denial. Or perhaps it was fear of losing the business they had worked so hard to make a success.

However, the Oster/Zimmermann family made it clear that they were not after reclamation. They wanted recognition. Not only for themselves but for the Jews of the region who built the industry in the 19th century that others now are benefitting from. They did not want their history to be erased. It was that simple. And that profound.

After a year of deliberation this story has a very happy ending. So does history. There is now a Jewish presence on the Royal Tokaji website, though only in English not in Hungarian.

June 24th at 11am there will be a ceremony in Mád. Several family members will travel to Hungary for it. These two plaques—in both languages—will be hung in full view. L’chaim.

Comments are closed.